“Lockdown reminded us that we’re all makers – and that could change everything.”

Artists in Isolation

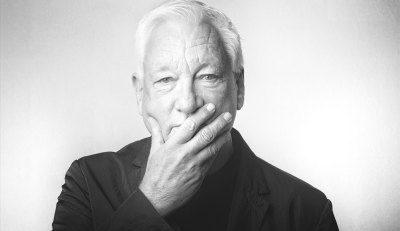

By Antony Gormley RA

Published 20 July 2020

“Lockdown reminded us that we’re all makers – and that could change everything.”

As museums and galleries reopen, Antony Gormley reflects on a revelatory three months in lockdown – and a cultural shift that could change the arts for the better.

-

This is the longest in years that I’ve spent in one place. We came to Norfolk in mid-March. I’ve watched Spring arrive and the cherry trees blossom, then leaves appear on the horse chestnuts, oaks and sycamore. I’ve seen my latest granddaughter, who was barely a month old at the start of lockdown, transition from this mewling puker into someone awake to the world, delighting in eye contact and talking to the trees from her cot as leaves move, silhouetted against the sky above her head. I’ve made work in my studio. I’ve lived with that work, and have had the time to reflect on it and on my job as an artist.

My life over the last 30 years has been spent zooming around the globe doing stuff. I have been extremely lucky to do it and it’s been terrific fun and very engaging. But it’s not necessary. In fact, I see now that that frantic way of living can be distracting and destructive. It’s part of a culture that, for so many reasons, fundamentally needs to change. Given the joys of the internet and the tools of communication now available to us, we’re never going to lose the knowledge of global culture. But this is a time in which creative diversity and the particularity of singular places needs to be given an impetus.

-

What would it mean if all children grew up feeling that potential to act in and on the world? The situation is changing.

-

The good news is, I think that change has already begun. Despite the daily pressures people have faced during lockdown, for me the most wonderful thing that has come out of this period is to see so clearly that everybody makes things. In so many homes, the family kitchen has become a studio – people have been sitting at their tables drawing and painting and making stuff. There’s been a realisation that actually, everyone enjoys that sensation of messing about with a box of paints or a lump of clay.

This goes to the heart of what is, in my view, one of the most serious misconceptions of our time – the idea that there is any division between artist and audience. Over the past 250 years, we’ve come to believe that culture has to be administered to you by institutions, but that doctrine is a very modern invention. Once art was Stonehenge, or the Stones of Stenness, or the Great Stupa in Sarnath or the Sleeping Buddha of Polonnaruwa. It was about creating something with the affordances of a place, local materials and local energy, and leaving it there – making something that is a collective dialogue with those who encounter it over time. My works that connect most profoundly with community and place – Iron:Man, Havmann, Angel of the North and Exposure – have felt the most worthwhile.

-

Antony Gormley, Angel of the North, 1998.

Antony Gormley, Iron:man, 1993.

Antony Gormley, Exposure, 2010.

Antony Gormley, Havmann, 1994.

-

The cultural shift that has already seen people nurturing their own creativity in lockdown is a wonderful precursor for the big shifts that need to happen. Art is a place of radical possibility, in which anything can be imagined and then made real. What would it mean if all children grew up feeling that potential to act in and on the world? The situation is changing. Art, as the generator for new ways of looking and being, has an incredibly important part to play. The recent Black Lives Matter protests are a powerful reminder of the recognition that art can be used for coercion as well as compassion. Statues have always been lightning conductors for passions and political awareness, as well as maypoles around which civic memories and ritual revolve. I see the potential of imaginative objects in our daily lives to be a focus for positive feelings of hope and belonging.

This is our chance to ask again: who can be involved in art and how? How can we tap into the collective creative potential in all of us? There are some amazing outreach programmes involving communities and children locally and nationally. That provision needs to be increased, and the products of it have somehow got to be shared. Rather than dedicating such a high proportion of our spaces to the art of yesterday, perhaps we should think of putting more of it into nurturing the art of tomorrow.

The RA in particular, I think, has huge potential to lead the way in this transformation – it was founded to both be an art school and to celebrate and support the creativity of artists. Academicians should spend more time in the RA Schools – they are the greatest resource that the Schools have. Could Burlington Gardens be transformed into studios? Why not turn the Academy back into a place where the newest and most challenging directions in the art of our time are not only made but tested and shared with a wider world?

So far as I’m concerned, the implication of these weeks and days and months is that museums have to open their arms to the inherent creativity in all of us.

Interview by Louise Cohen