A beginner’s guide to Bill Viola

A beginner’s guide to Bill Viola

By Alice Primrose

Published 17 December 2018

Bill Viola is considered one of the most important artists of his generation. As the RA prepares to show his vast, immersive installations alongside works by Michelangelo, it’s time to brush up on your knowledge of this American video art pioneer.

-

His work explores life’s biggest questions

Mortality, resurrection, rebirth, transcendence, infinity, the abyss – Bill Viola’s art stares them straight in the eye. Take his three-metre-tall 1992 work Nantes Triptych, for example: a trio of video panels show a young woman giving birth, the artist’s elderly mother the week before she died and in between, a clothed man floating suspended in dark, bubbling, otherworldly water.

Born in New York in 1951, Viola says his upbringing wasn’t particularly religious, but he’s spent four decades steeping himself in spiritual traditions. While in his early twenties working at one of Europe’s first video art studios in Florence, he frequently visited the city’s cathedrals. He later spent 18 months studying under a Zen Buddhist teacher in Japan, as well as travelling throughout Asia and the Pacific – including the Solomon Islands, Java, Bali, Ladakh and Fiji. When his work Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water) was inaugurated in St Paul’s Cathedral in 2014 (the first ever moving image work to be permanently installed in a British church), the Reverend Canon Mark Oakley said that “the rumour of God is very loud in [his] work”. But Viola leaves this “God” undefined by orthodox religion. Instead, as the Reverend said: “he offers us a shared way into the mysteries” .

-

Nantes Triptych

Watch an extract from Bill Viola’s Nantes Triptych, which is coming to the Royal Academy for Bill Viola / Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth.

Bill Viola, Nantes Triptych, 1992

Video/sound installation

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

-

He’s been called an Old Master of the video age

Viola has been called a “Rembrandt of the video age” and a “hi-tech Caravaggio”. Like the Old Masters, Viola is interested in how the aesthetics of his art can create profound emotional experiences.

In one of his best-known works, The Sleep of Reason (1988) – which is coming to the RA – visitors encounter a lit room containing a chest on which are placed domestic objects including a small monitor showing a man sleeping. Suddenly the whole room is plunged into darkness and overwhelmed with erratic projections of nightmares on the walls: blazing fires, fierce dogs, dark forests. As the artist says: “It is as if a momentary glimpse of another, parallel world has appeared, the dark underside of a familiar, well-lit environment”.

A pioneer of his medium, Viola has spent 40 years developing ways to make video works of overwhelming scale, technical skill and affective intimacy. Arriving at Syracuse University’s art school in 1969 he first studied commercial art and experimental music, but was soon tempted by the first portable, amateur video cameras that were arriving on the US market. Since then, his career has risen as quickly as video’s ever-evolving tools. He represented the United States at the 1995 Venice Biennale, and his artworks have been credited with offering the public “a kind of bridge” into cutting-edge video art. As the Observer art critic Laura Cumming said: “Viola has been using the newest technology to stir the oldest of emotions”.

-

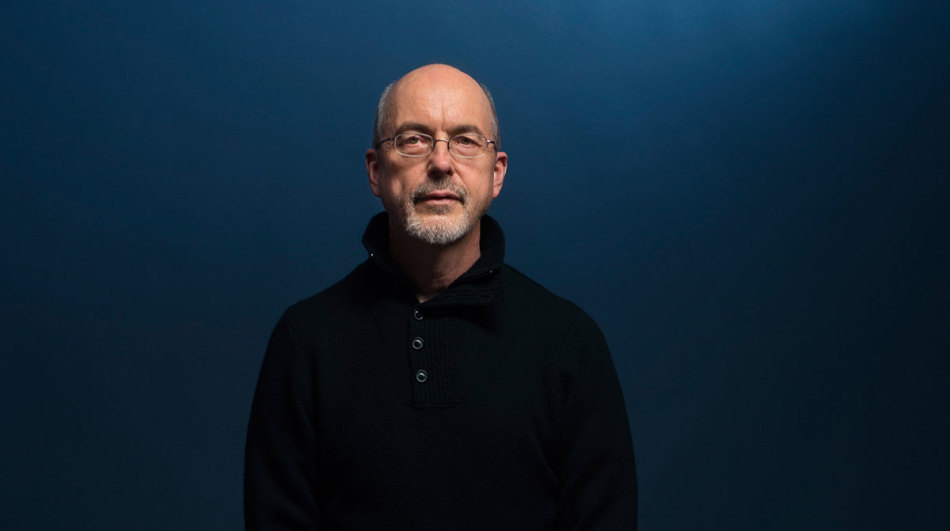

Bill Viola

Hubert Fanthomme/Paris Match/Contour by Getty Images

-

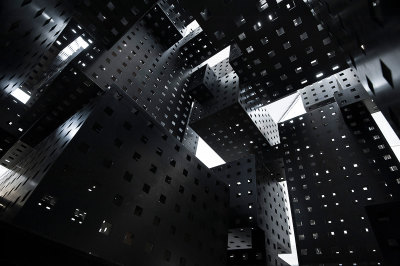

…But he doesn’t see himself as a “video artist”

“People say ‘oh it’s a video’ or ‘oh it’s a plasma screen’, but what I work with is light. I work with pure light” says Viola. You might get a sense of that while staring up at the glistening cascade of water in a six-metre-high projection like Tristan’s Ascension, one of 12 Viola artworks that will immerse the RA’s Main Galleries in deep darkness and dazzling light. His installations are inspired by the extravagant interiors of Florence’s pre-Renaissance cathedrals, where he first experienced artwork as a “sensory, visceral … physical, spatial, totally consuming experience” . So what is it that’s kept video central to Viola’s practice? “Moving images take time, and that is what I hope I can give to the viewer; time for reflection and most importantly, for self-reflection,” he told Wallpaper magazine. The artist’s interest in spirituality is really an interest in how we understand ourselves, and he has made video a useful tool in that pursuit.

-

…And he hasn’t always felt an affinity with art history’s pantheon

He admits of his younger self: “As an artist, I was always looking into the future. I didn’t give a shit about those guys!” But after the death of his mother in his forties, Viola recalls how seeing a painting of a crying Madonna by 15th-century Flemish painter Dieric Bouts “opened up a whole new dimension of grief” and with it a new appreciation for Old Master works. Since then, he has revelled in being “the heir to a long tradition of affective art” – as curator Martin Clayton puts it – stretching back to the emotional realism of early Renaissance artist Giotto. That tradition also includes Michelangelo, whose works on paper captivated Viola when he saw them in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle in 2006. Clayton, who showed Viola a selection of the Renaissance master’s drawings, had noticed that “there were many commonalities between the themes running through Bill’s works and underlying concerns that preoccupied Michelangelo”. Over 10 years later at the RA, both artists’ work is illuminated by the similarities between them.

-

Bill Viola, Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall), 2005.

Bill Viola, Fire Woman, 2005.

-

The four elements are central to his work

Viola’s art is filled with earth, wind, fire and water – the four elements that ancient Greeks believed make up everything else known to humankind. Curator Martin Clayton has suggested that working with what some believed to be the most basic components of the universe is a way for the artist to “create a physical analogue for the spiritual… the manifestation of the divine in the material”. Viola says he’s also interested in the physical possibilities of these elements – particularly fire and water – “their destructive aspects… their cathartic, purifying, transformative, and regenerative capacities”. In his 2005 work Fire Woman, for example (coming to the RA), a towering wall of what the artist calls “flames of passion and fever” roars behind the silhouette of a woman until she collapses into her reflection in a pool of water. Viola describes the work as the mind’s eye of a dying man as he realises that “the body’s desires will never again be met.“

-

Watch an extract from 'Five Angels for the Millennium'

Bill Viola, “Departing Angel”, panel 1 from Five Angels for the Millennium, 2001

Video/sound installation

Performer: Josh Coxx

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

-

He often works with bodies in physical extremes

His videos often focus on a singular body in a particular, extreme state – swimming, drowning, searching, dreaming, floating, gasping for breath, giving birth, being born or dying. Like his exhibition counterpart Michelangelo, Viola is interested in the relationship between the physical body and the soul, and how expressive bodies can convey inner spiritual states.

The bodies in his works mostly belong to performers – who act as stand-ins for all of us – although they aren’t always performing. Viola talks to those he’s enlisted about their deep personal experiences, but often doesn’t give an exact run-down of what will happen during the shoot, so many of the intimate close-ups you see projected in his installations are genuine emotional and physical reactions. The musician Weba Garretson had appeared in Viola’s works for nearly a decade (spot her in Surrender at the RA), but she still found that the water cascading over her in The Return (2007) was a “purification” that helped her through grief for her mother’s recent death. As Viola says, he wants his performers and his viewers to have an experience “in the present tense”.

Bill Viola / Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth is in the Main Galleries from 26 January — 31 March 2019.