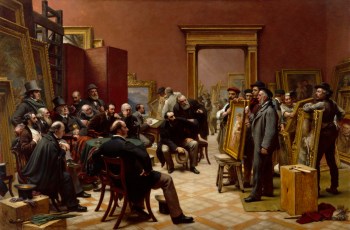

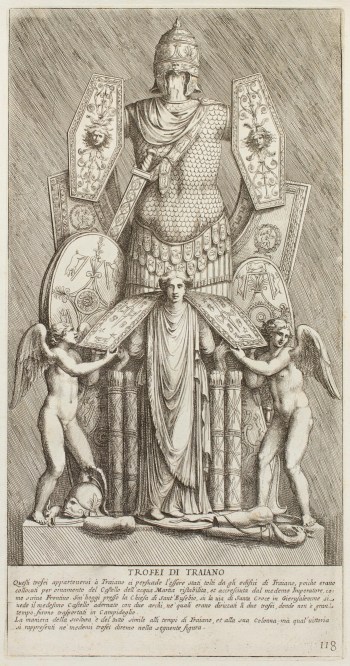

Artists often design monuments, plaques, trophies and medals as a form of public recognition and reward. These are a common feature of most towns and cities. Some are commissioned by the government, while others are more community-led.

These objects celebrate or commemorate a person or a group of people and can also include statues, war memorials, historic buildings, and sites of cultural or archeological significance.

War memorials usually celebrate a victory or commemorate those who died as a result of war while statues typically represent historical or living statespeople, religious or cultural figures, or royalty.

For different reasons all throughout history, during revolutions, regime changes, protests, and even natural disasters, statues have been erected, altered, damaged, removed, and replaced.

Because values change over time, statues that were put up in the past might represent people or events that we might not want to celebrate today.

Along with designing and producing visible rewards, artists have also had to question how we recognise and value success and achievements.

Learn together

Let’s see how:

• Public sculptures and monuments commemorate people and events

• Medals are awarded

• People are rewarded

Make it your own

Using readily available materials like cardboard, paper, tape, and glue, make statues of people who are important to you. Get other people to guess who they are.