Is it essential to see a painting in the flesh?

Is it essential to see a painting in the flesh?

Debate

By Emyr Williams and Sam Riviere

Published 27 August 2015

Does our perception of a painting rely on the electricity of human encounter? This week’s writers battle it out. Read both sides then vote below…

-

From the Summer 2015 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

-

Yes...

Paintings can only reveal themselves if we commune with them in person, argues artist Emyr Williams.

Joan Miró once said of Courbet’s painting, A Burial at Ornans (1849-50), “You can feel its power with your back turned to it.” As a schoolboy this remark had intrigued me, my sole reference for the Courbet being a small reproduction in a book. It was only when I saw the painting as an art student that I realised what had so overwhelmed Miró: the mourners are life-size. The sheer scale and ambition of this work is staggering. Conversely, the jewel-like qualities of a small Manet flower painting are dazzling in their modesty. A few years ago I had a visceral need to see and feel the scale of the huge Delacroix works in the Louvre. No other experience of them would do; I simply had to go to Paris.If you have ever watched a person looking at a painting, it is noticeable how mobile they are, often shifting their weight, or tilting their heads, as if attempting to locate something. Active looking is very physical, yet more paintings are probably seen nowadays digitally than “in the flesh”. For many, the convenience of a screen image suffices. Apologists will argue, convincingly, that our interaction with the virtual is an inevitable point on the trajectory of our developing human intelligence and culture.

-

Reproductions can be an aide-memoir... yet the electricity of the encounter is missing

-

Indeed, virtual realities are vitally useful in numerous disciplines – surgery springs to mind immediately. But is there a dehumanising flipside to this technological revolution? Are we disconnecting ourselves from the handmade? Are thousands of years of evolution culminating in our opposing thumbs’ ability to screen swipe?

I believe a painting cannot fulfil itself as “Art” unless one really sees it in person. Reproductions can be an enticing reference or an aide-memoir, yet the electricity of the encounter is missing. A real painting possesses an inherent plasticity formed through human endeavour; it provides us with a haptic sensation of constructed space. Furthermore, we often return to seemingly familiar works only to discover new and unforeseen qualities in them. This regeneration can only happen when our eyes apprehend the surface. The surface: that magical membrane, the point at which the paint stops and the air begins.

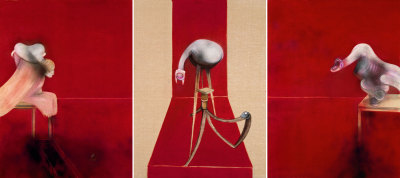

In this digital age, painters can ask themselves a simple, significant question: what can I achieve in this medium that I cannot do more effectively in another? As an abstract painter I now feel an urgency to make highly spatial paintings through a very specific control of colour and surface. Colour for me is completely dependent upon surface to make it both physically and emotionally expressive. I am always astonished at how a seemingly innocuous material such as paint achieves such amazing outcomes when handled sensitively. The “coloured glues” of paint, when viewed in reality rather than reproduction, can conjure up wonderful luminous spaces that condense and amplify the sensations we have of seeing and perceiving the world.

A painting for me should aspire to these heightened states of visual stimulation, rather than display itself as a form of entertainment or rely on extrinsic narratives, which other media can employ more readily. Painting needs to seek out more profound visual territory to explore. In any quest to advance painting, artists can learn illuminating lessons from the past. Matisse’s phosphorescent Venice interiors; Cézanne’s revolutionary landscapes; Constable’s daring spatial structures; Titian’s unerringly inventive compositions: all these feel more relevant than ever when seen in the flesh.

Great paintings like these provide a communion that is timeless. The transmitted backlight of a screen or the glossily inked page of a magazine homogenises our spatial perceptions and transforms “looking” into “reading.” To engage fully with a painting, we need to see its space… in its space. If we forsake opportunities to absorb ourselves in art in this way, we will surely erode one of the more remarkable abilities of our species.

Emyr Williams is an abstract artist.

-

No...

Our preconceptions prevent us from truly seeing an artwork, even when we stand before it, says poet Sam Riviere.

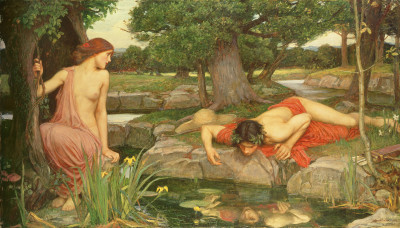

Last year I visited New York for the first time, a city synonymous with its galleries. Over a long, rainy Saturday in the Met, I was struck by one painting: Caravaggio’s The Holy Family with the Infant St John the Baptist (1602-04), and spent a while trying to work out why. At first it was Mary’s oddly averted gaze, but then, I thought, it was her age. Joseph is an old man, she looks about 12. What was that about? And was it the painting “itself” I was responding to, or rather its deviation from my “Children’s Bible” image, in which Mary and Joseph looked like my Mum and Dad, freaked out by parenthood in their late 20s. I had to admit it was also possible that I was misreading the work completely. How much additional knowledge did I need to assure myself that my interpretation was, let’s say, not incorrect? I had the familiar feeling that I was “reading” the painting, not “seeing” the painting.This was a continuation of an argument I have been having with myself for some time: that despite having gone to art school, and apparently made art, I often remain sceptical about its effects. I’ve stood before work at private views, wondering what the acceptable amount of time is to stay there, before, with that turning half-step indicating both reluctance and saturation, moving on. This feeling intensifies in large galleries, where it’s coupled with the battle not to continually refer to the text next to the pictures. I suspect I still spend more time reading in galleries than “seeing.” The Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz can be my guide here. He wrote in his Diary (1953-69) how the apples and sunflowers of Cézanne and Van Gogh leave an “enormous gap” in our understanding of them, only compensated for by their biographies. “If the word had not conveyed their lives to us,” he added, “there’s not much we could do with their self-portraits.”

New York’s Museum of Modern Art, with its avant-garde work from the 20th century, is less overwhelmingly historical than the Met, but when I visited it, I felt even closer to Gombrowicz’s cynicism. Its visitors ranged blindly through the rooms, each I suppose hunting for some singular scrap of meaning. A tiny percentage is able to appreciate the significance of most of these works, yet everyone who goes to New York goes there. What exactly is it selling? Come in, Witold: “You err in thinking that the paintings themselves are a revelation and that is why people look at them… Just the opposite has happened.”

At the Frick Collection I wanted to see The Polish Rider (c.1655, often attributed to Rembrandt), because of a poem by Frank O’Hara: “I would rather look at you than all the portraits in the world / except possibly for the Polish Rider occasionally and anyway it’s in the Frick” – itself a hymn of life over art, where portraits become “just paint / you suddenly wonder why in the world anyone ever did them.”

-

I’ve stood before work at private views, wondering what the acceptable amount of time is to stay there.

-

I had a sad time, mainly since no-one was there being garrulous and legendary, least of all Frank O’ Hara, and the fact that so little is known about the painting just made it easier to incorporate into my selfish New York micro-narrative. This story isn’t really about the painting at all – what interpretation could be more facile than that?

In order to “see” The Polish Rider, I had to know it already from online image searches and O’Hara’s poem. Maybe I was simply recognising the painting rather than “seeing” it, as if from my approach it was somehow hidden by its own image. Maybe “seeing” a painting is really a way of providing evidence for the frameworks of meaning we already have in our heads. Maybe no “essential” seeing is even available, and a painting is visible only to the extent that it complements your existing knowledge – a kind of accessory.

Sam Riviere is a poet. His collections include Kim Kardashian’s Marriage, published by Faber.

-

-

Enjoyed this article?

Become a Friend to receive RA Magazine

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door.

Why not join the club?

-