‘Le Mystère Picasso’

Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up. — Pablo Picasso

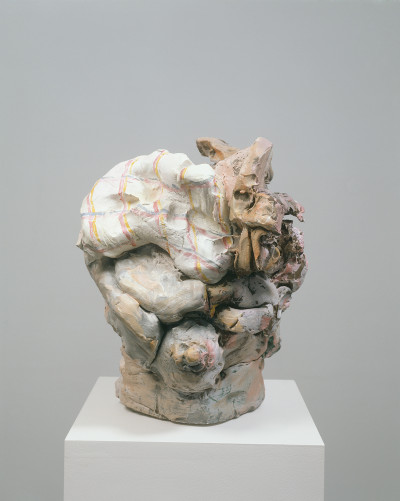

In this video, Picasso demonstrates the importance of play: watch as his drawing evolves from flower, to fish, to chicken, to face, before it becomes the head of a faun.

Try experimenting with making instinctive changes to a drawing:

• start with a speedy doodle and see what animal you can turn it into

• play a game of ‘consequences’ by passing a drawing around the class, each child adding to it or transforming it into something new