Georg Baselitz: Artist and collector

Georg Baselitz: Artist and collector

An interview with the Honorary Royal Academician

By Dr Christian Weikop

Published 28 March 2014

Georg Baselitz first encountered chiaroscuro woodcuts on a trip to Italy as a young artist. He went on to become an avid collector of these revolutionary prints, many of which are now on display in our exhibition ‘Renaissance Impressions’.

-

Art historian Dr Christian Weikop talks to Baselitz about his experiences of Italy, his own practice as a printmaker, some of his connections to Expressionism, and his relationship to Anselm Kiefer, whose work will be shown in a major forthcoming retrospective at the RA.

Christian Weikop: Emil Nolde, an artist with whom you have sometimes been compared, and who similarly took his name from his Heimat (homeland), would later reflect on the time he spent in Italy (1904-05) stating ‘Artistically, that country gave me nothing’. However, this does not seem to have been your experience. What impact did Italy have on you in the mid-1960s?

Georg Baselitz: For me, Italy had a reviving effect. The country seemed totally intact as far as the historic buildings were concerned. During that time (1965) Germany was still ruined, especially Berlin where I was based. In Italy, the Renaissance was something almost tangible. To be able to appreciate undamaged buildings that were well over one hundred years old, this made a huge impression on me.

CW: When in Florence, did you find yourself more drawn to the artistic style of ‘Mannerism’ than art from an earlier period?

GB: At that time I was very much influenced by a book, Gustav René Hocke’s Die Welt als Labyrinth, a vital, intellectual and philosophical book. That was my bible in Florence. Before reading this I had never heard of Parmigianino, Pontormo, Rosso, Bronzino and so on. With this book I sought out this form of art in churches and museums, travelling around by bus. It was really a completely new and interesting world, in contrast to the Classical. After these experiences, I intensified my studies by attending the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence. In the photo archive, I studied the printmaking of this period about which I knew nothing before. Until that point, I was uneducated and unaware of other printmakers beyond Dürer and Rembrandt … I returned to Berlin, where I tried to obtain more information about these Renaissance prints and there I made my first acquisitions.

• View two examples of Baselitz woodcuts from this period on the National Galleries of Scotland website and National Gallery of Australia website

CW: When I visited the British Museum yesterday to see your own prints in the exhibition Germany Divided: Baselitz and his Generation, I was reminded of your connection to another Saxon artist, Adrian Ludwig Richter. Your work is often discussed in relation to a German visual canon, but what about your particular Saxon identity? Do you see yourself in line with artists such as Cranach, Friedrich, Richter, the Brücke artists, Dix, Kokoschka, I mean artists who were born and raised, or who lived and worked in Dresden and other places in Saxony?

-

Hendrick Goltzius, Landscape with Trees and a Shepherd Couple, c. 1593-98.

Chiaroscuro woodcut printed from three blocks, the tone blocks in pale green and green. 11.7 x 15.3 cm. Collection Georg Baselitz. Photo Albertina, Vienna. Organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London and the Albertina, Vienna.

-

GB: The references to Ludwig Richter in my work were critical and cynical. I had no real appreciation for German artists who went to Italy and imitated Raphael. That seemed somewhat suspect. Raphael was the main focus of interest for nineteenth-century German and English artists. I saw this and I didn’t like it … I am a German artist, but I am intrigued by the nature of cultural exchange. I know that Dürer had close contacts to Italy, but he didn’t paint in an Italian manner in Italy, neither did Campagnola make his prints ‘German’ in Germany. Each retained their own style, personality, and world of ideas, and yet this contact to another culture was enriching.

CW: What about printmakers of the Northern Renaissance, for instance, Hendrick Goltzius?

GB: The spontaneity and creative directness of Goltzius’s approach to printmaking interested me greatly, there was no division of labour in the printmaking process; the print was not simply used as a reproductive method, but had great artistic validity. He worked with the same directness as I do today.

-

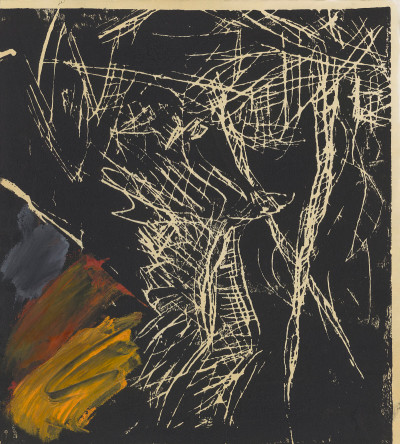

Georg Baselitz, Fliegender Adler (‘Flying Eagle’), 1977.

Georg Baselitz, Adler (‘Eagle’), 1981/82.

-

CW: When I look at your own woodcuts I can see traces of Mannerism, but also in your rough-cut approach there seems to be some kinship to the early work of a Brücke artist like Erich Heckel, almost as if Mannerism has been filtered through Expressionism, or perhaps vice versa.

GB: In the late 1960s when my work started to become better known, critics started to refer to me as a ‘Neo-Expressionist’. I did not like such a label, but I came to accept it.

CW: Did you ever collect Expressionist prints or did you focus exclusively on Mannerism?

GB: I have never collected prints from other periods. My passion started in Florence with Mannerism and at times stopped due to a lack of money or interest, and then I took it up again. In the last twenty years this collecting has become more intensive. My passion is not shared by anybody; it is some kind of idiosyncrasy.

CW: I know you have a great interest in the work of Edvard Munch, but did his prints interest you as much as his paintings?

GB: Munch is exceptional, but where do you place him? He is not an avant-garde artist, he is not a traditionalist, but he is an extraordinary and incomparable artist. How does an artist become successful in their work and yet not be understood as avant-garde? I have come to appreciate that ‘avant-garde’ is a problematic term. For many years, I have looked at the work of British artists such as Freud, Auerbach, and Bacon. What is avant-garde about them? Nothing. Some years ago, I would have said that they are not contemporary artists, but the paintings that they created are contemporary and wonderful. Whereas someone such as Pechstein, very active in the avant-garde circle of the Brücke, was a mediocre artist and nobody talks about him anymore. It is a complicated matter.

CW: Remaining on the subject of collecting art, last October I travelled to Paris to interview Anselm Kiefer in preparation for the forthcoming retrospective here at the Royal Academy. Kiefer told me that you were very generous in supporting his early career and that you were the first to buy his paintings. I know you acquired a number of his ‘Dachboden’ (Attic) canvases from the 1973 14 mal 14 exhibition in Baden-Baden, curated by Klaus Gallwitz. What first attracted you to these large canvases by Kiefer?

GB: This was the first time that Kiefer’s paintings had been exhibited and I was completely fascinated. It was the first time [said with a wry smile] that I found myself face to face with such incredible works that I had not produced myself! This enthusiasm continues to this day; it has not faded but increased. Kiefer trained in Karlsruhe and then became a mentee of Beuys. Beuys is an artist to whom I felt some considerable distance rather than any close connection, but that is not the case with Kiefer. He is a truly genuine artist with an incredible soul, and his paintings, these early paintings, leave such an impression because of their physical presence. I had never seen such paintings before …

CW: While your interest in all things arboreal may predate Kiefer’s, I am very interested in your shared preoccupation with the German forest both in your work and your life. It intrigues me that in 1971 you both chose to live in forest regions (not so far from each other), and that you both set up studio spaces in old school houses.

GB: At this time, Kiefer was much more intellectual than me. He had a good education, spoke several languages, whereas I had nothing like that. I was really a man out of the forest! I was rather ‘Dumm’ like Simplicius [said laughing]. Grimmelshausen was my central point of reference! Kiefer’s forests did not interest me particularly, and I knew his references to Wagner. What interested me was the formal language of his painting, which was so extraordinary. These were very powerful canvases possessing an incredible presence and they seemed to spring out of the frames.

CW: Can I ask you about some of the distinctions between your attitude to printmaking and Kiefer’s? He started in the woodcut perhaps eight years after you, but his approach seems very different. Looking at old photographs of his studio, his prints are strewn all over the floor. His woodcuts are re-utilised in many works and are not editioned. Would it be true to say that your practice is perhaps closer to an Expressionist artist such as Kirchner in stressing the importance of the original print and the significance of each impression?

GB: Kiefer used his prints for illustrative purposes – and I don’t mean this in the negative sense, as documents in a larger conceptual context. I have never used my prints like that, but rather in a more traditional context. Don’t forget when I was producing these woodcuts it was in the days of screen printing - it was the beginning of Pop Art. At home I had a screen print of a tea bag by Oldenburg on the wall, and next to it a work by Gerhard Richter titled Queen Elizabeth II. This was modern art, but I wanted to create something that was not ‘modern art’. One way to do that was to delve back into history and rediscover the woodcut, and suddenly you were in the Middle Ages! This was some distance away from Lichtenstein and company. What is far away from modern art? Mannerism is far away, I didn’t really have Expressionism in mind. I found the prints of Hans Baldung Grien and Burgkmair to be wonderful, but I did not produce woodcuts in imitation of theirs; it was more of a provocation.

CW: But nonetheless having seen your 2007 exhibition A Bridge Ghost’s Supper in Berlin, there does seem to be some connection or kinship between you and the likes of Schmidt-Rottluff, Kirchner, and so on.

GB: No, back then I decided to look at Nolde, Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff – and yes, they had something in common with me, but my heart wasn’t in it. As Kiefer created his woodcut collage of portraits with an air of detachment so I maintained a certain distance. I trained to paint those portraits as well as I could so that the figures were recognisable as Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, and Munch. That was the intention. Like Kiefer, I put the portraits together and used them in an illustrative sense.

-

Georg Baselitz, BDM Gruppe, 2012.

Cast in bronze from an original carved in wood. 366 x 242 x 149 cm. © Georg Baselitz 2014. Photo credit: Jochen Littkemann.

-

CW: Finally, I wanted to ask you about the connection between your woodcuts and wood sculpture. Your large-scale carvings have always reminded me of the primitivising work that Kirchner produced in Switzerland with his disciples from the Rot-Blau group, except of course that you often you use a chainsaw as well as an axe.

GB: Have you been there? [to Kirchner’s former home at Wildboden, near Davos]. It is now owned by Eberhard Kornfeld and it is incredible. There is of course a connection between woodcut and wood sculpture, but when I made the early sculptures in the late 1970s I was not a professional, rather I was an amateur working in wood. Now I am a professional and I have developed a considerable career as a sculptor. In the last year I have made such fantastic sculptures, which I couldn’t imagine producing back then. The process becomes more and more interesting … You do not have to start at the age of 20; you can start when you are 70! It is a curious path.

Dr Christian Weikop is a Chancellor’s Fellow in Art History at the University of Edinburgh. He is contributing to the catalogue for the forthcoming Royal Academy exhibition Anselm Kiefer (27 September – 14 December 2014).

Translated by Christian Weikop.