Joseph Cornell and his poets

By Tamar Yoseloff

Published 17 June 2015

The Ted Hughes Poetry Prize-nominated author and leader of our Joseph Cornell-inspired short course explores the poets whose writings had a profound effect on the artist.

-

Perhaps no other artist of the 20th century was so indebted to the poets he read and loved as Joseph Cornell. Cornell was profoundly influenced by poetry; he understood that poetry attempts to construct a concise framework that contains the world. He was a voracious reader, collecting poets from both Europe and America, much as he collected objects on his scavenger hunts around New York to use as source material for his work.

Cornell’s earliest poetic discoveries were the French Symbolists, and he was drawn to the imaginative worlds of Guillaume Apollinaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and Gérard de Nerval. Nerval, the Parisian dandy who famously walked his pet lobster on a leash around the Palais-Royal, explored the provisional world between reality and dream in his short prose piece, Aurélia. In the following passage, Nerval could easily be describing Cornell’s shadow boxes and their fantasy visions, nearly eighty years before their creation:

“Dream is a second life … Little by little, the dim cavern is suffused with light, and emerging from its shadowy view … the tableau takes on shape, a new clarity illuminates these bizarre apparitions and sets them in motion – the spirit world opens for us.”

-

Lee Miller, Joseph Cornell, New York, 1933.

Joseph Cornell, Toward the Blue Peninsula: for Emily Dickinson, c. 1953.

Joseph Cornell, Naples, c. 1942.

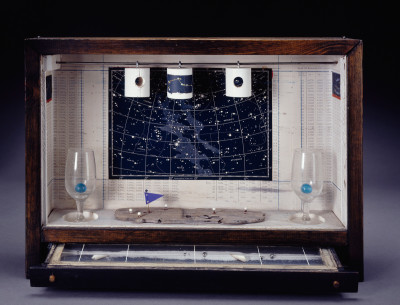

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Celestial Navigation), 1956-58.

-

Other European poets Cornell admired included Federico García Lorca, Dante and Friedrich Hölderlin, whose words and images permeated his boxes and collages. But it was the American poet Emily Dickinson with whom Cornell felt a particular affinity. He devoured biographies of her, identifying with her quiet home life and the expansive wanderings of her imagination. Dickinson was reluctant to allow many of her poems into the public realm, just as Cornell would hoard his shadow boxes in the basement of his house on Utopia Parkway in Queens, unwilling to sell them. Cornell dedicated his work Toward the Blue Peninsula (pictured above) to Dickinson, with a nod to her lines:

I am not used to Hope –

It might intrude upon –

It’s sweet parade – blaspheme the place –

Ordained to suffering –It might be easier

To fail – with Land in Sight –

Than gain – my Blue Peninsula –

To perish – of Delight –But Cornell didn’t just revere poets of the past. He and the American poet Marianne Moore enjoyed a long and lively correspondence, and shared a mutual interest in dance, animals, birds and exotic civilisations. Moore expressed “ever grateful wonder” for Cornell’s work. The heroes of the New York School in the 1950s and 60s, Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, wrote both poems and criticism in praise of Cornell, with O’Hara calling him a “pure and uncompromising spirit”. Ashbery wrote that “we all live in his enchanted forest” and dedicated his poem, Pantoum to the artist. Here are the opening lines:

Eyes shining without mystery,

Footprints eager for the past

Through the vague snow of many clay pipes,

And what is in store?

-

Dream is a second life . . . Little by little, the dim cavern is suffused with light, and emerging from its shadowy view . . . the tableau takes on shape, a new clarity illuminates these bizarre apparitions and sets them in motion – the spirit world opens for us.

Nerval

-

Long after Cornell’s death in 1972, poets remain in his debt and continue their tributes. Jonathan Safran Foer’s Cornell-inspired anthology A Convergence of Birds contains work by a collection of distinguished writers, including Rosemarie Waldrop, Robert Pinsky, John Yau and Siri Hustvedt. Robert Coover and Charles Simic have devoted entire collections to the artist. Simic’s book, Dime Story Alchemy, includes the poem Secret Toy which perfectly encapsulates Cornell’s playful and mysterious process:

Everything in his world is a secret, and the games are

still the game of love, the game of hide-and-seek, and

the chilly game of solitude.Simic describes in his introduction how Cornell’s working methods inspired his own poems: “Cornell worked in the absence of any aesthetic theory and previous notion of beauty. He shuffled a few inconsequential found objects inside his boxes until together they composed an image that pleased him with no clue as to what that image will turn out to be in the end. I had hoped to do the same.”

-

Joseph Cornell, Tilly Losch, c. 1935-38.

Box Construction. 25.4 x 23.5 x 5.4 cm. Collection of Robert Lehrman, courtesy of Aimee and Robert Lehrman. Photography: Quicksilver Photographers, LLC. © The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/VAGA, NY/DACS, London 2015.

-

Cornell continues to inspire and encourage that spirit. His work, so much of it encased in small glass boxes which might be seen to emulate the proportions of a sonnet, is concerned with containment and preservation. That is all we can ever hope for as poets – that our disparate images, our snippets of memory, our reveries and realities, might come together and form a cohesive whole. The exhibition Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust, will give us a new opportunity to respond creatively to his intricate vision.

Tamar Yoseloff led the short course Containing the World in Words: Poetry and Joseph Cornell, which ran from 29 June – 27 July 2015. Three poems written during the course are reproduced below:

-

-

In the Royal Academy, dreaming of coffee and cake

for Joseph Cornell and Derek Mahon

In a one-inch pillbox, whose marbled wall

has no beginning or end, two small screws

lie together, nestling in a shadow-edged

oblong of reflected light. From the New Worldthey crossed an ocean to this city, whose

imperial pink once covered the Mercator globe;

soon they will find themselves in another

white room, in the city of Mozart, of kaffee undkuchen, Anschluss and suffering (the orchestra

plays on). On the floor of the pillbox they dream

of these things, and of their fellow creatures

on the next island, abandoned by the colonistin a disused shed, craning at the door

for a glimpse of the keyhole-shaped sky.Nora Hughes

-

Joseph Cornell In Robert’s Model Train

I love this train. Always ride in the same

compartment where the tall barred windows cast

faint grids of light across the floor and frame

the shifting phases of the moon. The past

flickers by like scenery, repeating

familiar images, some clear, some blurred -

a palace, sand between my toes, beating

wings, the back of an insect, soft and furred.

I scan the turning world for mystery,

the places where I’ll never disembark.

I criss-cross centuries of history,

the burning desert and the frozen dark.

This tiny carriage gives me ample space

to hold the universe in my embrace.Doreen Hinchliffe

-

The Window

(After Palace and Gnir Rednow by Joseph Cornell)

dances with gold – an embarrassment of riches.

We can’t see outside it, beyond us – the world

made up of bone-brittling scarceness. Struggle:

a word we have never had to define. Our story

unchanged throughout generations, privileged

and private – the way we’ve lived out our lives

behind mirrored glass. We keep the known safe.Behind mirrored glass we keep the known safe

and private – the way we’ve lived out our lives

unchanged throughout generations. Privilege:

a word we have never had to define. Our story

made up of bone-brittling scarceness, struggle;

we can’t see outside it. Beyond us, the world

dances with gold – an embarrassment of riches.Ruth Steadman

-