How to be an armchair voyager like Cornell

How to be an armchair voyager like Cornell

By Harriet Baker

Published 3 July 2015

A unique figure in American art, Joseph Cornell worked in his own, extraordinary medium – the shadow box. Now we’re inviting you to capture your dreams in boxes too, in our Instagram challenge.

-

Joseph Cornell was a gaunt man with steely grey hair who never spent a night away from home. Even before he became an artist, he was a collector. At the house he shared with his mother, he worked in a tiny basement studio cluttered with archive boxes, dossier files and small objects – feathers, pipes, shells and marbles – all labelled in an idiosyncratic fashion.

It was from this unusual collection of objects, which he found all over New York City, that Cornell created something profound and new, in whimsical assemblages of found objects and images. His unusual oeuvre included collages and montage films, but among his most compelling works were his intriguing box constructions – a form that went on to inspire contemporary artists including Mariele Neudecker and Mark Dion, and a legacy seen in installations by Damien Hirst and the vitrines of Edmund de Waal and Anselm Kiefer.

What is a shadow box?

Simple, glass-fronted, wooden cabinets, “shadow boxes” have their origins in Victorian crafts. Throughout the nineteenth-century, across Europe and America, it was a common hobby for women to fill these cases with keepsakes: shells, ships and dried flowers. They were sentimental objects, intended to preserve an atmosphere or a particular time or person. Shadow boxes are still popular today, particularly in America, both as a traditional form of arts and crafts and as a way of paying tribute to sporting or military heroes.

-

A traditional shadow box

Image courtesy of Flickr user Nina Helmer, Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

-

Putting things in boxes first occurred to Cornell during one of his city jaunts in the 1930s after he had seen a display of compasses in a shop window: “I thought, everything can be used in a lifetime, can’t it, and went on walking. I’d scarcely gone two blocks when I came on another shop window full of boxes, all different kinds… Halfway home on the train that night, I thought again of the compasses and the boxes. It occurred to me to put the two together.” (Life, 1967)

Compasses, of course, were just one of a plethora of items that Cornell collected and arranged to create the ideas, places and people captured inside his shadow boxes. He would scour the dime stores and antique shops of Manhattan for second-hand books and unusual objects; he bought buttons from haberdashery counters and coloured sand from pet shops. In an interview for Life magazine in 1967, Cornell said: “I collect anything of human interest. There are no elite kinds of things in my work.”

Initially, Cornell bought pre-made containers, such as oriental boxes, commercial packaging, scientific specimen cases, and antique jewellery boxes, as a starting point for his assemblages. Later, he fashioned his own boxes from wood and glass. The result was works such as those in Cornell’s Aviary series of the 1940s, in which paper parrots and cockatoos perch in wooden structures surrounded by small drawers and arrangements of corks. Elsewhere, Cornell revealed his love of cabinets in Pharmacy (1943) and L‘Égypte de Mlle Cléo de Mérode cours élémentaire d‘histoire naturelle (1940), in which glass vials contain magical substances in gleaming rows.

-

I collect anything of human interest. There are no elite kinds of things in my work

Joseph Cornell, Life, 1967

-

What was Cornell trying to do?

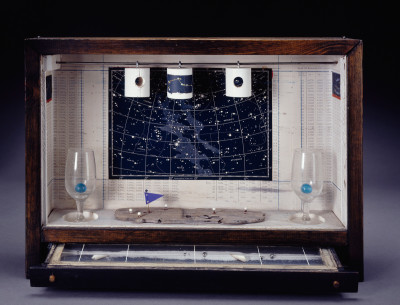

Any categorisation of Cornell as an artist remains a matter of dispute: some view him as a Dadaist (he met Duchamp in the 1930s and the pair had a long correspondence), while others argue that his juxtaposition of images and objects was derived from Surrealism (one of his collages was shown in the ‘Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme’ at the Galérie Beaux-Arts in Paris, organized by André Breton, author of the first Surrealist manifesto if 1924). But Cornell’s affiliations and influences came from far and wide, and that diversity is reflected in his boxes; symbolic appropriations of objects that mesh high art with pop culture. He was equally inspired by Renaissance imagery and the slot machines on Coney Island, by ballet and by beach combing.That he visited the opera and the ballet in New York is not surprising, as his miniature dioramas also recall stage sets with a scenic and narrative quality. As Mary Ann Caws writes in Joseph Cornell’s Theatre of the Mind, “Cornell’s shadow boxes invite us to peek, to peep, and finally to yield to our imagination… We meet in the confines of this tiny frame, this microcosm of complicity.” The boxes are filled with potential energy, as if just about to move, and are spaces in which multiple scales co-exist: time and history, the natural world and the cosmos. They are places of curious juxtaposition: take Untitled (Celestial Navigation) (1956-58), in which the universe is depicted through everyday objects.

-

Joseph Cornell, Tilly Losch, c. 1935-38.

Joseph Cornell, Naples, c. 1942.

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Pinturicchio Boy), 1942-52.

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Celestial Navigation), 1956-58.

-

As the curator of the RA’s exhibition, Sarah Lea, explains: “Boxes allowed Cornell a structure to frame many poetic connections between disparate times, subjects and places that he sensed in the world. Given the extent of his collection, each of his shadow boxes is a major feat of distillation. Within the imaginary space of the box, objects take on metaphorical meanings.”

To what extent was Cornell engaging with the Victorian, feminine connotations of shadow boxes? “Cornell has often been criticised for being sentimental to the point of saccharine,” says Lea. “But also he said, “The dialectics of nostalgia intrigue me,” and so we can see that he’s aware of this sentimentality in his work. He’s exploring the idea of what it is to be nostalgic, that is, how we experience the world around us through our own memories, and how objects and images are vehicles for this - he was deeply interested in the passage of time.“

In notes that Cornell wrote to accompany one his box constructions, we see that he perceived these artworks to be distillations of his nostalgic past and his imagined future:

-

Impressions intriguingly diverse – that, in order to hold fast, one might assemble, assort, and arrange into a cabinet – the contraption kind of the amusement resorts with endless ingenuity of effect, worked by coin and plunger, or brightly coloured pin-balls – travelling inclined runways – starting in motion compartment after compartment with a symphony of mechanical magic of sight and sound borrowed from the motion picture art – into childhood – into fantasy – through the streets of New York – through tropical skies – etc. – into the receiving trays the balls come to rest releasing prizes.

Joseph Cornell

-

Though his work was made from the streets of New York – a city he never left (after the death of his father, Cornell devoted himself to the care of his mother and brother) – Cornell perpetually returned to the idea of travel. He described himself as an “armchair voyager” and his shadow boxes are filled with the imagery of travel. Take Naples (1942), a narrow box containing a wine glass backed by a print of an Italian street scene, a microcosm of a distant city. On top of the box is a suitcase handle, and dangling within is a luggage label. The box is a voyage in itself.

He used maps, compasses, timetables, postage stamps and hotel advertisements of places he would never visit. He was also interested in the freedom of birds to travel vast distances and in their migratory patterns – as in Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery (1943) – and he explored the idea of space through images of stars and astrological charts. Through his shadow boxes, he travelled to distant realms, collecting imaginary souvenirs from imaginary voyages.

The Cornell Instagram challenge

In celebration of Joseph Cornell, we launched the Cornell Challenge on Instagram, asking users to create their own shadow boxes using the Instagram square as their display case. Instagrammers were invited to collect and assemble small objects and images to portray a journey, a particular time or person in their lives. This challenge has now closed. Take a look at the winning entries…

-

Instagrammers from around the world take part in the Cornell Challenge

@bookbw

@eileen_cooper_ra

@foundandchosen

@karajshaw

@koehuckle

@learosa2

@handmadeincalcutta

@obaker2

@prusko_artist

@rareradish

@short.brooks

@phoebe__

-

Video

Joseph Cornell: armchair voyager

The title of our Joseph Cornell exhibition is ‘Wanderlust’. Curator Sarah Lea describes how this theme is closely linked to Cornell’s artistic practice, and his travels of the imagination.

-

Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust will be in the Main Galleries until 27 September 2015.