A beginner’s guide to Lucian Freud

A beginner’s guide to Lucian Freud

Published 22 October 2019

As we unite more than 50 of Lucian Freud’s self-portraits for the first time ever, here’s a handy guide to get to know the man whose painted, printed and drawn figure is in our galleries this autumn.

-

He is one of art’s most influential portraitists

Lucian Freud (1922–2011) changed how we look at people. He filled his canvases with bodies rarely given space elsewhere: fat bodies, ageing bodies, queer bodies, exhausted bodies. Some have described his portraits as ruthless, pitiless, clinical and cruel; others see them as intimate and honest records of humanity. He once described himself as “a sort of biologist”, interested in “the insides and undersides of things”. Freud turned his scrutinising eye on his own changing body at every stage of his life, experimenting relentlessly with strange angles and arrangements that pushed the boundaries of self-portraiture. Fellow artist Antony Gormley has described Freud’s practice as a “resilient exploration as witness to those around him and to his own existence”.

-

-

He was an adopted Englishman

Freud was born in Berlin in 1922 to a Jewish family (which included his grandfather, the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud), but they left for London when Hitler came to power 11 years later. Freud spent the rest of his life in the capital, befriending people from all corners of society for his portraits. He could often be found drinking and betting in Soho’s bars and clubs from the 1940s to the 1960s, or (towards the end of his life) having long lunches with eccentric Londoners at The Wolseley, a lavish restaurant just around the corner from the Royal Academy. As an adult, Freud said that moving to England was “Linked to my luck… London, the place I prefer in every way to anywhere I’ve been.”

-

-

-

He tried to live a private life… but failed

Freud claimed that “My first word was ‘alleine’ which means ‘alone’. ‘Leave me alone’: I always liked being on my own.” When people tried to take his photograph, he quickly shielded his face with his hand (he did this even in his official photo with the Queen when he accepted his Order of Merit – though she used the image for her Christmas card that year anyway). He rejected the idea that an artist’s life mattered to his art and rarely gave interviews, but his creative legacy is entwined with stories of his personal exploits. He used some of his 14 (acknowledged) children as sitters for paintings, but was far from a conventional father figure (“communal life”, he once said, “has never had much appeal”). He made Self-portrait with a Black Eye just hours after a fist fight with a cab driver. In his only piece of writing on his own art, Freud wrote that “A painter must think of everything he sees as being there entirely for his own use and pleasure”, and he lived by that principle his entire life.

-

-

-

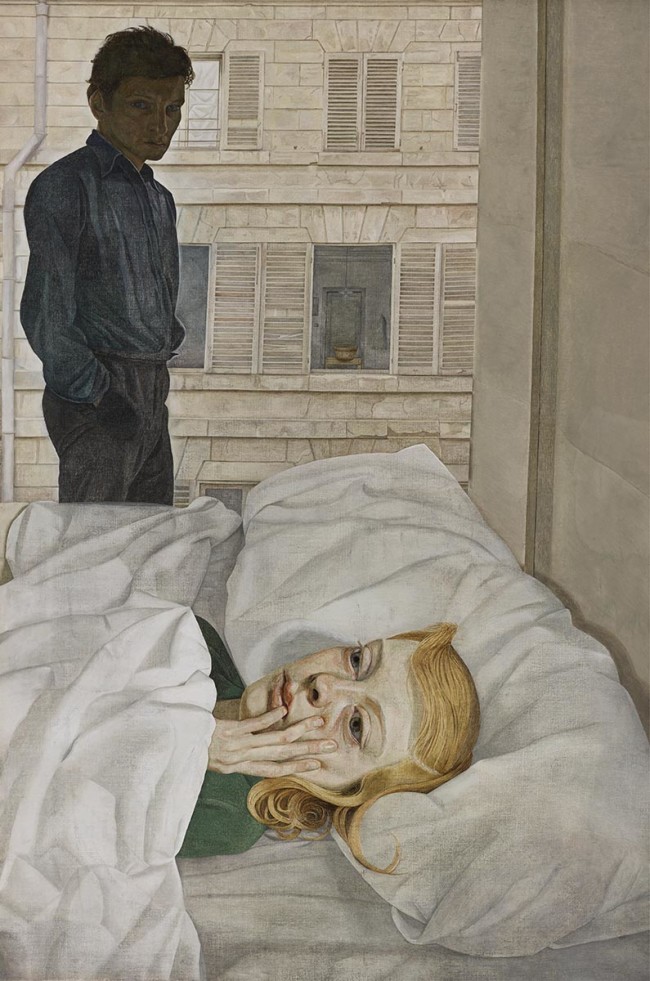

He didn’t always paint those notorious nudes

In his early career Freud took influence from Surrealist artists who depicted a reality made strange. Their practices were in turn greatly informed by texts written by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud – the artist’s grandfather. Like the Surrealists, Freud combined detailed observation with an unsettling sense of not-quite-reality. His portraits were linear, graphic, clean and precise – and his subjects were dressed. In his 40s, after years of scrutinising sitters for hours each day (often perched just a foot or two away, with the canvas balanced on his knees), his eyes were exhausted. As a result he slowly started painting more loosely and freely. He swapped his brushes from soft sable to bristly hog’s hair snipped down to a stub. He started layering canvases with thick, clotted paint. He decided that “I want the paint to feel like flesh”, and the more painting he did, the more flesh there was. As he came to realise: “I am really interested in people as animals. Part of my liking to work from them naked is for that reason. Because I can see more.”

-

-

He painted more than 160 people

…including Queen Elizabeth, though she remained fully clothed. She joined Freud’s motley crew of performance artists, members of the criminal underworld, Lord Rothschild, a restauranteur, Kate Moss, a jobcentre manager, duchesses, drag queens, some of his 14 children, his mum, and himself. He worked on three or four portraits at once, with each subject painted for hours at a time over several years (many were positioned lying down so they could sleep while he worked). He demanded that his models were “punctual, patient and nocturnal”. The artist David Hockney RA (who sat for Freud for 120 hours in 2002) told Vanity Fair, “I was fascinated by his process… He wanted you to talk so he could watch how your face moved. He had these incredible eyes that sort of pierced into you, and I could tell when he was working on a specific part of my face, my left cheek or something. Because those eyes would be peering in: peering and piercing.”

-

-

His self-portraits span his career

From his first self-portrait at age 17 to his final one executed 64 years later, Freud committed himself to canvas throughout his life. To do so, he said, “you’ve got to try and paint yourself as another person”. His studio assistant of 20 years, David Dawson, once said that “It’s heavy going for him psychologically, but he sees it as a sort of a duty.” He refused to paint from photographs, since “the aura given out by a person or object is as much a part of them as their flesh. The effect that they make in space is as bound up with them as might be their colour or smell.” Instead, he often painted his reflection using mirrors of various sizes – and included references to this in both the works and their titles. Ultimately, he said, an artist should be present in his work “no more than God in nature. The man is nothing; the work is everything.”

-

-

-

See Lucian Freud's self-portraits at the RA

27 October 2019 — 26 January 2020

In a world first, this autumn we’re uniting Lucian Freud’s self-portraits in one extraordinary exhibition. See more than 50 paintings, prints and drawings in which this infamous figure of British art turns his unflinching eye firmly on himself.

-