Behind the scenes in Britain’s oldest art school

Behind the scenes in Britain’s oldest art school

By Sarah Handelman

Published 17 June 2019

The RA Schools has been nurturing, challenging and championing art students for 250 years. Before work begins on a big anniversary renewal, we took a look inside to find out what it’s like studying there in 2019.

-

From the Spring 2019 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA. This issue is an arts education special, to mark the 250th anniversary of the RA Schools.

-

A school run by artists

In early January the Keeper and the academic team of the Royal Academy Schools met to shortlist the 769 applications they had received for the upcoming year. Over two weeks they discussed and debated the merits of each portfolio until they had agreed on about 65 candidates to invite for interview in February. Out of this number, they would offer no more than 17 places in what is the longest running art school in Britain.

Being the oldest does not automatically make it the best, but for more than two centuries the Schools of the Royal Academy has certainly held a unique position when it comes to the education of artists. During its 250-year existence, the RA Schools has, like the Academy itself, maintained its independence – through income from sales of works in the Summer Exhibition, but in more recent decades primarily through the generosity of the Schools’ network of patrons and supporters, bequests from the public and, from this year, the support of RA250 Members. The Schools in turn extend that independence to the small group of art students who are accepted onto its three-year postgraduate programme: there are no tuition fees, there are bursaries for living expenses, and everyone has their own studio – unheard-of elsewhere in Britain, where a one-year MA can cost around £10,000 in fees alone.

No wonder, then, that more people apply each year. Although this makes for more work for the admissions panel, “it means that you can get a much more diverse group of people applying”, says Margarita Gluzberg, who joined the RA Schools last September as Senior Lecturer. “It provides opportunities to those who wouldn’t be able to afford a postgraduate degree. A lot of people just cannot embark on that path.”

-

Student Millie Layton working in her studio at the RA Schools, 2019. All students are given a free studio space for their three years at the Schools

© Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Benjamin McMahon

-

The approach is not just about creating a level financial playing field. There are also no formal criteria for judging work, which means there is no precedent or expectation about what kind of artist can or should apply. “We are very conscious of having an inclusive and diverse group of artists, not just in terms of who they are and where they’re from but also what they make,” says Brian Griffiths, Senior Lecturer for third-year students.

This wasn’t always the case. Historically the RA Schools was known as a home for painters and sculptors, but by the 1990s, it was increasingly overlooked for failing to reflect changes in the discipline, as more artists looked to performance, new technologies, installation and more material experimentation in making their work. The Academy finally caught up under the leadership of Brendan Neiland, Keeper between 1998 and 2004, when the programme adapted to contemporary art practice. Today it is once again one of the most respected places for artists to evolve. “Everything is secondary to the individual students who come to study and contribute to our programme,” says Richard Kirwan, Senior Lecturer of the second-year students. “It’s the student group who influence and determine the direction of the Schools.”

This viewpoint is integral to the selection process. After the quality of a prospective student’s work has been taken into consideration, a second concern arises once they have been shortlisted: how they will sit and engage within their year group. “It’s not about necessarily finding the best work – although you hope the work is really good and substantial – but also how it could evolve in a place like this,” says Gluzberg. That place is something inherently difficult to describe. To the uninitiated, art school is an enigma – a place of creative blocks and breakthroughs and moments of genius.

-

Students Toby Jury Morgan and Amanda Kyritsopoulou in the wood workshop at the RA Schools, 2019

© Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Benjamin McMahon

-

Gluzberg likens the RA Schools itself to a ship, and it’s tempting to wonder whether its architect Sydney Smirke RA had a nautical flair. Smirke’s original 1868 scheme was designed as a single floor, with one studio flowing into the next; and the Life Room as a central point where students could convene. Astonishingly, there has been no refurbishment of the RA Schools since it was built; ad-hoc structures have simply accumulated over time: mezzanines accommodate editing suites, a corridor serves as the library, prints are dried in a makeshift closet, a temporary shed (erected in the 1990s) houses several workshops, and a galley-like canteen and bar host lunch and drinks in the evening. With equal exasperation and endearment Eliza Bonham Carter, Head and Curator of the Schools, describes these accretions as “barnacles”, adding to the building’s ship-like character. Not an image of contemporary art school architecture – with its vast volumes of adaptable space – but something more specific and enigmatic. Captain Nemo’s submarine Nautilus – another 19th-century construction largely hidden from view – comes to mind.

With the Royal Academy’s redevelopment opening up more of its interior as public spaces, the Cast Corridor, which had once been tucked away completely, is now revealed either side of the junction between the Julia and Hans Rausing Vaults and the airy Weston Studio. Any visitor walking between Burlington House and Burlington Gardens will encounter that corridor, and a glimpse of life in the RA Schools.

Clearly, the Schools spaces in the Academy have long been in need of development too. The RA Schools is planning its own metamorphosis: its first modernisation since 1868. The new scheme, led by David Chipperfield RA, will restore the historic spaces of the Schools, enlarge its artist studios, house a new library and make the entire premises – renamed the Julia and Hans Rausing Campus – completely accessible for disabled artists and visitors. Workshops will be relocated across the courtyard, encouraging a new flow between spaces and among RA Schools students and staff. “The workshop spaces will just be better for everyone to use,” says Sculpture Workshop Manager, Richard Elliott. “You cannot get anyone using a wheelchair into the workshops – many of them are accessed via staircases. The new masterplan will solve that.” And it will enable the Schools to continue to bring the most diverse artists through its doors.

-

A stash of paint and pencils in the RA Schools, 2019

© Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Benjamin McMahon

-

Room for robust discourse

The students here are from a wide age range (the youngest is 23, the oldest 42), a wide demographic, and they make a wide range of work. But for all their disparateness there is a certain consistency to how they describe the experience of being here. The word most used is “intense”. The artists are expected to be in their studios each day. Over three years they attend talks and lectures together, they have group critiques (or “crits”) where they comment on each others’ work, they have lunch together in the canteen, and they drink together in the bar – a closeness that is “the curse and blessing of the RA Schools”, says second-year Jenkin van Zyl.

Being here is “like having Christmas dinner with all your aunts and uncles every day”, says Hamish Pearch, a third-year student whose current work – models of agricultural architecture that combine with analogue image production – echoes the architecture of his own barn-like studio. “It’s people you grow to love, and you’re sitting down, you’re all talking, you have to walk past each other all the time. People sleep together. They fall out. Being here is great, but it’s intense.” The students I spoke to say that, as artists, they have directly benefited from having to work around people they did not choose themselves and to engage with work they might not choose to encounter.

“I’ve learned to be a bit more generous,” adds van Zyl, whose studio is as transgressive and otherworldly as the places he creates in his video work, with a disused theatre set from a Western forming the walls, bulbous silicone creatures and a wardrobe of wigs and costumes. “Before the RA, I was very particular about the type of work and subject positions I entertained. Being here has taught me that I can spend 90 minutes intimately discussing formal abstract painting – I still don’t enjoy being around it, but such debate certainly is a good tool.”

-

Student Jenkin van Zyl working in his studio at the RA Schools, 2019

© Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Benjamin McMahon

-

“The Schools are driven by the idea of robust discourse,” says Rebecca Salter RA. Guest editor of the spring 2019 issue of RA Magazine, Salter is the 25th Keeper of the Royal Academy, the Academician responsible for overseeing the Schools. She explains that talking about art – whether yours or another’s, at lunch, in a crit, in the studio or in passing – is a way of getting closer to knowing why anyone makes art in the first place.

That kind of openness to discussion and difference is a defining trait of the Schools and, Salter argues, can be traced back to its earliest years. Unlike other schools throughout Europe, the pedagogy was never shaped by a single vision of the Keeper; instead a revolving door of Visitors guided students. Today, as well as the Senior Lecturers and workshop tutors, students have unparalleled access to a stream of visiting artists, makers and curators, invited by both tutors and the students themselves.

“I’ve had some amazing and pertinent conversations about the work I’m making, not just with tutors and visiting artists, but with my peers,” says Jala Wahid, who is now in her third year. “It has really accelerated my practice. Before coming to the RA, being in my studio was so isolating. I could go days without speaking to anyone. Now I can just turn around and someone is there. That is not something to be underestimated. What the RA offers beyond anything else is a community. That is the one of the most important things art education can provide.”

-

Dinnertime in the RA Schools canteen, 2019, where students get subsidised meals and a space to talk over the day

© Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Benjamin McMahon

-

A practice for practice

During their time at the RA Schools, students are liberated from the two biggest pressures they face as artists in London: money and space. For first-year student Hannah Farrell, coming to the RA Schools meant relocating from Manchester to London, where it is expensive and time-consuming to find housing: “My first month in London was spent couch-surfing. I didn’t have any of my belongings. I didn’t have anything from my studio in Manchester. I couldn’t really think about making work. But the Schools made it clear that their help was there if I needed it.” By December, though, Farrell felt settled and was meeting with a workshop tutor to construct a purpose-built still-life studio for her photographic work.

Unlike one-year MA programmes, which are the norm at other institutions and which can sometimes seem finished before they’ve even started, having three years of study creates less pressure on students when things don’t go to plan. “The three years give people a chance to understand the way they work and the way they think, and enough time to put that into practice before trying to push that position out into the world, which is really difficult but necessary,” says Griffiths. “A lot of artists have to block out the noise, or the particular dominant ways of thinking in contemporary culture, to be able to focus on what’s important to them. Finding your pace and rhythm as an artist can be hard.”

“That’s probably why there will be real highs and lows here,” says Farrell. “It’s like you’re shedding your egoic tendencies. You’re constantly observing things about yourself and your practice that you need to let go of.”

For another student, three years has been enough time to experience both the extremes of prolificacy and feeling utterly blocked. After a first year of “non-stop” making, she felt stuck. Too anxious to be in her studio, she found herself in the workshops, testing materials. “My tutors would ask me what I wanted to make and I’d say, ‘Nothing – I don’t know what I want to make. I’ve exorcised everything from my brain. There’s nothing left.’ One tutor told me that this is life as an artist. You have times when you are really productive and flowing, but you also have times when things are really dull and there’s nothing going on and you just have to go through it.”

-

A student works on a sculpture at the RA Schools, 2019

© Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Benjamin McMahon

-

“One of the biggest challenges is how to survive in the art world as an artist,” says Alison Myners, Chair of the RA Development Trust, and the person who, 20 years ago, helped spearhead the RA Patrons scheme that now helps ensure that the Schools remain a tuition-free course. “Three years affords you opportunities. Risk and failure are integral parts of the development of artists, and the second year here, especially, allows for time to fail, for crises, for time to rip up work, and for time to say, ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I can’t cope.’”

It also allows the time to dig deep. An exhibition held halfway through the second year, Premiums: Interim Projects, is essential in this process – a pivotal moment for students to reflect on what they’ve been doing, and to envisage where they want to go. A range of support, from monetary prizes and travel scholarships to bursaries made possible through donations and legacies, are awarded to students at the end of the exhibition, allowing them to invest more time, energy and material into their work. On the back of last year’s Premiums, Wahid received a travel bursary, which she used to visit her family in Kurdistan, and to reengage with the surrounding landscape. She is now utilising these connections in her final year at the RA Schools, and her studio is filled with tests of casts exploring how to convey what she saw while travelling. An oversized tongue of an ox, based on ones she had seen in a market in Kurdistan, has been cast in a range of materials, from Jesmonite to wax glass.

“In a way, because the Schools until recently has remained so hidden, it has been slightly cocooned,” continues Myners. “But in order to raise the support we need – and to ensure that the Schools remain non-fee-paying – we need to allow for a wider level of accessibility. This affords an opportunity for the artists to come out of that cocoon and to filter into all areas of the Royal Academy. And without interfering in the creative process, it also offers a chance for the people who can support the Schools to engage.”

-

Student Clara Hastrup tests out new work at the RA Schools, 2019

© Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Benjamin McMahon

-

By taking part in events such as the Keeper’s Dinner, held at the beginning of each school year, as well as studio visits and the annual auction that benefits the RA Schools, the students develop a confidence in speaking about their work with an audience that represents a key part of the art world. At the same time, supporters gain rare insights into young artists’ practice. “Because there are few students at the Schools, the relationship you can build with the Royal Academy and those students is pretty incredible,” explains May Calil, a long-time supporter and now a Schools Ambassador.

Another major influence in the life of the RA Schools is, of course, the Academy itself: its location, its history and the artists behind it. “The main thing about being a student in the RA Schools is that you have a special privilege,” says the fashion designer Paul Smith, who with his wife Pauline supports one student through their entire time at the Schools. “With the location in Piccadilly and the luminaries who have been through the Academy – it’s just so full of energy. If you walk through the front entrance and go up the stairs, you can walk past a Gustav Klimt or Leonardo, depending on what’s showing, on your way to school. That’s not bad, is it?”

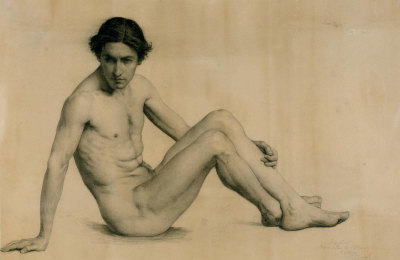

It’s a fact that is not lost on the students. “It takes real strength to keep an institution like this going for so long,” says Farrell. “Every time we see the shows upstairs, spend time with the RA Collection, use the archives and even the Life Room, we have the opportunity to tune into a lineage of people who’ve dedicated their whole lives to art. I really like that idea.”

-

Sarah Handelman is Deputy Editor of RA Magazine.

RA Schools Show 2019 is at the RA from 20—30 June 2019.