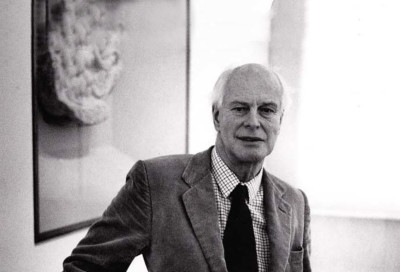

Sir Michael Hopkins RA (b. 1935)

Michael Hopkins, with Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and Nick Grimshaw was one of the driving forces behind high-tech architecture, though he was the first of this quartet to broaden his palette of materials and forms in the mid 1980s. Having spent some time in partnership with Foster after studying at the Architectural Association and a spell with Frederick Gibberd, he started his own practice with his wife Patty in 1976. One of their first buildings was their own house in Hampstead, an elegant, lightweight structure with minimal steel and glass facades. Many of their early projects were industrial, a purpose which seemed well suited to the ethos of high tech, and the Schlumberger Research Laboratories outside Cambridge (1985) take the logic of this form of lightweight, masted construction to a fine pitch of expressiveness.

Almost immediately afterwards Hopkins won a competition for the new Mound Stand at Lord’s Cricket Ground. Although its tent-like fabric roofs have something in common with Schlumberger, its base is a rebuilt brick arcade dating from the early 20th century. At Bracken House in the City of London, a new structure fills in the space once occupied by the Financial Times’s printing presses between two wings with curving stone, metal and glass facades, which both reflect the building’s original model and recall the best early examples of office design. Commissions like the new opera house at Glyndebourne and the Queen’s Building at Emmanuel College Cambridge confirmed Hopkins ability to match new with old, both in construction techniques and relating tradition to contemporary uses.

Two issues in particular show how Hopkins has challenged conventional architectural wisdom. The first is in showing how lightweight steel-and-glass structures can be energy efficient. A factory for Solid State Logic and a later building for Schlumberger both use the thermal mass of a heavily sculpted concrete floor slabs even out extremes of temperature, while the external appearance is of pristine, glass boxes. The second is in adding new dimensions to the expressive potential of traditional crafts like masonry and carpentry by using contemporary engineering skills. The stone pillars at the Queen’s Building, for example, can be especially slender because they contain post tensioned steel rods.

From these two themes Hopkins weaves an architectural language which is unmistakably contemporary, but while satisfying modern expectations can also relate comfortably to historic contexts. He has designed discreet visitors’ facilities within the cloisters of Norwich Cathedral, and made more overtly contemporary additions to the Victorian Classical core of Manchester City Art Gallery. With its two storey mansard roof and tall chimneys, the New Parliamentary Office building nods towards the context of Norman Shaw’s New Scotland Yard building, while also expressing the energy strategy that means it uses about one third of the energy of a similarly-sized conventional office.

Profile

Born: 1935 in Bournemouth?, Hampshire, England, United Kingdom

Nationality: British

Elected RA: 28 May 1992

Elected Senior RA: 1 October 2010

Gender: Male

Preferred media: Architecture