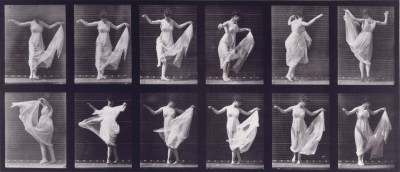

John Gibson RA, Phaeton driving the Chariot of the Sun, After 1846.

Plaster relief. 1105 mm x 2265 mm. © Photo: Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photographer: Paul Highnam.

This image is not available to download. To licence this image for commercial purposes, contact our Picture Library at picturelibrary@royalacademy.org.uk

Phaeton driving the Chariot of the Sun, After 1846

John Gibson RA (1790 - 1866)

RA Collection: Art

This plaster relief is believed to be the model for the marble relief that Gibson executed for Earl Fitzwillliam. The composition is one of a pair, its companion piece is 'The Hours leading the Horses of the Sun' and a plaster of this subject is also in the RA Collection (RA 03/2044). Marble versions of both scenes exist at Fitzwilliam's mansion Wentworth Woodhouse, Yorkshire and in the collection of the National Museums of Wales, Cardiff.

Earl Fitzwilliam's visit to Gibson’s studio in Rome is recorded in at least two 19th-century sources (Lady Eastlake's Life of John Gibson of 1870 and the Art Journal article 'A Walk through the Studios of Rome' of 1854). According to Gibson's own account, cited by Lady Eastlake, Fitzwilliam originally intended to commission two large bas reliefs depicting 'a subject from the history of England, with knights on horseback in armour'. Gibson declined this subject, which lent itself to a Gothic treatment, explaining that he had 'great admiration' for the horses but 'objected to the knights'. The armour, he argued, would make it impossible for him to convey ‘the beauty of the human form’ according to Classical principles.

Instead, Gibson showed Fitzwilliam his book of designs, including a drawing of ‘The Hours and the Horses of the Sun’ (see RA 05/475). Fitzwilliam returned to Gibson’s studio with his daughters and asked to see the sketch once again. In his 1911 biography of Gibson, Thomas Matthews cited more of the sculptor’s recollections of this meeting with the Fitzwilliam family describing how ‘Lady Charlotte began to admire it, dwelling upon it, and then Lady Dorothy and Lady Albreda [Alfreda]; in fact Lady Charlotte advised her father to have it executed. It was decided upon, and I have spent a long time in modelling that work, and although I had made many anatomical studies of the horse, I still made more dissections, and also studied from the life.’ (Matthews 1911, pp.140-141).

The date of this commission was previously given as 1826 but this seems to be incorrect based on the established date for the companion work (which was exhibited at the Royal Academy annual exhibition of 1849) and on the evidence in correspondence between John Gibson and Margaret Sandbach now in the National Library of Wales. The latter suggests that Fitzwilliam's visit to Gibson's studio in Rome took place late in 1846 (see discussion in Sculpture Victorious, New Haven and London, p. 191).

Gibson wrote to his friend Mrs Sandbach on 6 March 1847 about the pendant relief stating that, aside from anxieties about his brother's ill health, he was completely preoccupied by this bas-relief for Earl Fitzwilliam. He continued: 'it has so absorbed all my soul and busy that I have been as if shut up from the world, and from all that belongs to it. Still, mortality must come and interrupt me, and disturb my happy dreams. I, who have no wife nor child, nor dog, nor cat to draw my thoughts away from my art, have my brother, Mr. Ben, to trouble me. He has been ill for weeks…My present work, the model of the Hours, will be finished in three weeks. I have never done a work which has given me more pleasure than this. The learned and the unlearned seem struck with it. Wyatt says it is full of go. I work at it with delight, except my fits of trouble about Mr. Ben…’ (Lady Eastlake, 1870, pp.194-195). The catalogue entry for both reliefs in the Sculpture Victorious catalogue also mentions another letter of 21 September1848 in which Gibson states that he has begun work on the marble version of ‘The Hours’. On his next visit to England, Gibson visited Wentworth Woodhouse to see the two reliefs installed in the Marble Hall opposite each other above two fireplaces (see Matthews 1911, pp. 140-141 and Sculpture Victorious, p. 189).

Caroline Vout, writing in the Sculpture Victorious catalogue, notes that Gibson chose not to depict the Fall of Phaeton as many other artists had done but instead depicted this figure 'still trailblazing, his body all tension as he tries, in vain, to steady a cart for which he is too heavy' with the 'bulging calves and biceps of an exemplary male body'. She also notes that an Art Journal review of Wenzel and Prosseda's Imitations of Drawings by John Gibson RA Sculptor (London, 1852) described an engraving of Gibson's Phaeton composition as:

'the most effective composition of its class we have ever seen. The fire of the subject is thrown into the horses, which are skilfully modelled throughout with the utmost care. The animals are most skilfully disposed, and their action sufficiently declares their headlong career. The subject has been many times treated in Modern Art, but in this composition there are points which are unexcelled in any recent effort.'

She connects the specific interest in sculptures of horses to the high status of the Parthenon Marbles in Britain at this time. Gibson considered these sculptures to be 'the most valuable and interesting in existence' and studied casts after the frieze at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome.

Both plaster casts were acquired by the Royal Academy as part of the Gibson Bequest in 1866 and, from 1876, were displayed high up on the walls in the first room of the Gibson Gallery. Their presence is recorded in newspaper reviews of the new display and in plans of the layout for the gallery (see Frasca-Rath and Wickham, John Gibson: A British Sculptor in Rome, 2016, pp. 54-57).

Related works:

Marble versions at Wentworth Woodhouse and in the National Museum of Wales

http://liberty.henry-moore.org/henrymoore/works/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=12069&x=0

A drawing of the same scene signed and dated 1850 in the Royal Collection https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/search#/17/collection/913429/phaeton-driving-the- chariot-of-the-sun

This differs from the relief in showing Phaeton without drapery apart from his cloak but is possibly connected with the engraving of the subject published in Wenzel and Prosseda's Imitations of Drawings by John Gibson RA Sculptor published in 1852.

Further reading:

A. Frasca-Rath and A. Wickham, John Gibson: A British Sculptor in Rome, RA Publications, London 2016, pp. 21-22, fig. 15

See also http://www.gibson-trail.uk/works

M. Droth, J. Edwards and M Hatt (eds.), Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837-1901 , New Haven and London, 2014, cat no. 56, pp. 188-191

R. Gunnis, Dictionary of British Sculptors, 1660-1851 , London: The Abbey Library, [1953], p.173

T. Matthews, Biography of John Gibson, London: William Heinemann, 1911, pp.139-141, 243

Lady Eastlake, Life of John Gibson, R.A. Sculptor, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1870, pp. 85-86, 253

'British Artists: Their Style and Character, with engraved illustrations, No. XXVIII. - John Gibson, R.A.', The Art-Journal, 1857, pp. 273-275, engraved p. 274

Florentina, 'A Walk through the Studios of Rome', The Art-Journal , 1854, pp. 184-187, 287-289

Anna Jameson, Handbook to the Courts of Modern Sculpture, London 1854

Object details

1105 mm x 2265 mm

Start exploring the RA Collection

- Explore art works, paint-smeared palettes, scribbled letters and more...

- Artists and architects have run the RA for 250 years.

Our Collection is a record of them.