Video

Richard Rogers RA

A video introduction to the exhibition ‘Richard Rogers RA: Inside Out ’ at the Royal Academy of Arts in 2013.

When he designed the Pompidou Centre with Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers came closer than anyone to building the technological fantasies of the 1960s. It disappointed the Archigram Group, who had drawn many of those fantasies, only because it did not move. More recently Rogers has turned to masterplanning, urban design and the ecological issues of regenerating or creating ‘sustainable communities’, most cogently expressed in his Reith Lectures, published as Cities for a Small Planet.

The consistency which underlies this apparent paradox is the key to understanding Rogers’ architecture. For him the goals have always been social: the Pompidou Centre was conceived to re-fashion the whole notion of an art institution, to make art more accessible and invite mass participation in cultural activities. Technology, even architecture, is not the end in itself, but a means of achieving it, and the evolution of his work reflects the shift in perceptions of technology from an undiluted good to a problematic phenomenon. What has remained consistent is his firm belief that architecture is the most powerful facilitator of an equitable society.

Rogers came to Britain from his country of birth, Italy, as a refugee from Fascism. He studied at the Architectural Association and Yale, where he met Norman Foster with whom he founded Team 4. An obvious influence on their lightweight industrial aesthetic was the Californian Case Study houses, but after Team 4 split, Foster pursued its constructional logic, while Rogers worked on a series of lightweight capsule-like buildings with Piano and the Design Research Unit.

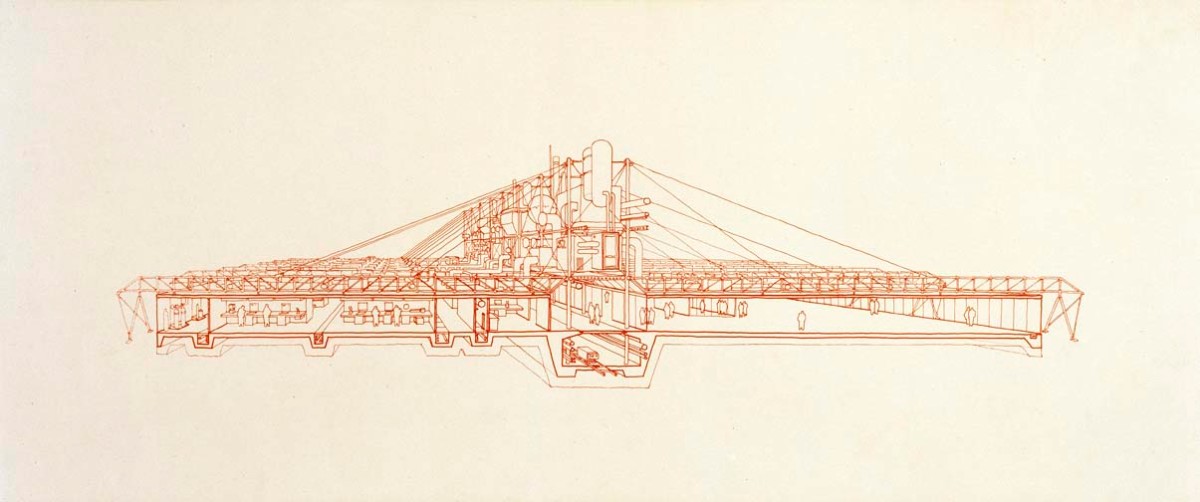

Winning the Pompidou Centre in 1971 (completed 1977) transformed his practice and reputation. In a series of buildings over the following decade, such as the Lloyd’s headquarters in the City of London, and the masted factory for the silicon chip maker Inmos, Rogers pushed the language of ‘high tech’ to its rhetorical limits. Although each element had at root some functional justification, it was as if the function were frozen in time. Technological advance rendered Inmos obsolete fairly quickly, while Lloyd’s for all its internal dynamism and external panache, offered few meaningful connections to its context.

By the 1990s Rogers’ work acquired new depths. A broader range of public commissions, from masterplanning to law courts, allowed him to develop his ideas about communities, while developments in materials and construction allowed powerful and transparent forms to meet new standards of energy efficiency. An unsuccessful competition entry for the Tokyo International Forum proposed new relationships between open public space, and the enclosures necessary for high art, themes which in different ways projects like an unbuilt canopy for London’s South Bank Centre and the Millennium Dome explore. Several recent commissions have shown Rogers to be a consummate commercial architect, but, as at Paddington Basin or Heathrow’s Terminal 5, always striving to include a mix of public and private interests.

Elected ARA: 11 May 1978

Elected RA: 9 May 1984

Richard Rogers RA, Design for Inmos Microprocessor Factory, Newport, Gwent, Wales: section perspective, 1980.

A video introduction to the exhibition ‘Richard Rogers RA: Inside Out ’ at the Royal Academy of Arts in 2013.

2008 Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour

2007 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

2006 Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement (La Biennale di Venezia)

2000 Praemium Imperiale Prize for Architecture

1999 Winner of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Medal

1991 Received knighthood

1986 Awarded the Légion d’Honneur

1985 RIBA Gold Medal Winner