Five minutes with Sonia Boyce RA

Five minutes with Sonia Boyce RA

By Aurella Yussuf

Published 3 March 2022

From her creative upbringing to a 20-year long art project, get to know the artist representing Britain at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

-

From the Spring 2022 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Aurella Yussuf is an art critic and founding member of the art collective Thick/er Black Lines

-

She was raised in a creative home

As a child, the artist was often drawing, designing and handcrafting household items with her siblings – her eldest sister, she recalls, had a flair for interior design. While making was part of her everyday life, it was a secondary school teacher who recognised her artistic potential and encouraged her to apply to art school. If life as an artist appears a somewhat enigmatic pursuit in 2022, it was even more mysterious to a young Boyce, growing up in London’s East End in the 1970s. She recalls her school careers advisor seeming even less informed than she was, and directing her towards millinery. “She said, ‘I don’t think you need any qualifications for that, do you?”’ and handed Boyce a postwar-era pamphlet.

-

She discovered the Blk Art Group at art school

Once she enrolled at Stourbridge College of Art in the West Midlands, Boyce became aware that image-making was something to be taken seriously, with the potential to make her a living. It was here too that she was introduced to the Blk Art Group, an association of four student artists (Eddie Chambers, Keith Piper, Donald Rodney and Marlene Smith) whose work turned a critical lens on race, class and politics in art and in wider British society at the time. The group’s 1981 exhibition Black Art An’ Done at Wolverhampton Art Gallery was a revelation: “It blew my mind,” Boyce says.

The following year, she attended the first ever National Black Art Convention, organised by the group at Wolverhampton Art School, along with over 200 Black artists from across the country. “It was quite a feat for the Blk Art Group to have organised something that significant as a group of students,” she recalls. “But it also says something about that time, that sense of ‘If you want to do something – just get up and do it’, rather than waiting for someone to allow or sanction you doing it.”

-

Adama Jalloh, Sonia Boyce RA, 2022.

Courtesy the Royal Academy of Arts, London © Sonia Boyce. All rights reserved.

-

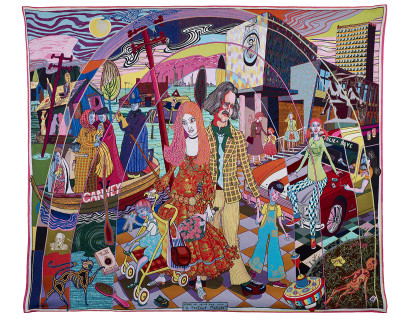

She was influenced by Frida Kahlo

Boyce cites the Mexican artist as a major inspiration in those early years, when she was making works on paper in which she featured herself as the central figure. Her 1986 drawing She Ain’t Holdin’ Them Up, She’s Holdin’ On (Some English Rose) shows a young Black woman, ostensibly Boyce herself, wearing a dress adorned with black roses while balancing a family of four above her head with her hands. “Kahlo’s works were autobiographical but she’s always performing in those images, and that’s what I was doing in those drawings.” This sense of the artist playing to an audience continued as Boyce shifted, in the early 1990s, away from the drawings for which she had become known towards a more collaborative way of working.

-

Kahlo’s works were autobiographical but she’s always performing in those images, and that’s what I was doing in those drawings.

Sonia Boyce RA

-

She's been working on a project about Black British female singers for 20 years

Boyce started her ongoing project Devotional, a collection relating to Black British female singers, with a memory of ‘Hurts So Good’ by Susan Cadogan, a lovers’ rock song that Boyce listened to as a teenager. She was struck by the gap between her recollection of the song and its actual lyrics: “The words themselves are very macabre, but because of the way the melody entrances you, I didn’t realise the depth of what she was singing about. I was interested in the starkness between those two spaces.”

The artist began working with a women’s group in Liverpool on an exercise memorialising the names of Black British female singers, and over the past two decades Devotional has grown to become a collection of over 300 names spanning the 19th century to the present day, as well as physical records and memorabilia. From this, Boyce has created a dynamic and ever-evolving artwork reinvented with each iteration, including as a sculptural installation of placards and wallpaper (2008–20). The work redresses a form of systemic amnesia that obscures the cultural contributions of these singers. “Naming the performer is like offering a portrait in some form,” she observes.

-

She gives her audience the space to play

Boyce has become increasingly drawn to the possibilities that improvisation offers, especially in how viewers respond to a moment of freedom within a situation she has orchestrated. “I’m always surprised and delighted by how inventive people are, particularly if they’re just given the space.” While details are strictly under wraps, this perhaps hints at what to expect from Boyce at the Venice Biennale this year, where the artist represents Great Britain.

-

She paves a way for others

Boyce doesn’t put much stock in being the first Black woman invited to represent the country in this way, but she sees the opportunity to lodge the door open for others. Her priority now, as always, is to keep the work itself at the forefront of the conversation. “The more Black artists talk about what we do, and the various meanings that can come from that, the better.”

-

-

Enjoyed this article?

Become a Friend to receive RA Magazine

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

-