The extraordinary life of Charles Stewart

The extraordinary life of Charles Stewart

By Harriet Baker

Published 19 December 2014

Charles Stewart’s illustrations to the Gothic novel Uncle Silas hint at an unusual life. Here are five surprising facts.

-

He grew up in an eerie castle

Charles Stewart’s obsession with the Gothic is perhaps unsurprising given his childhood. He was born in 1915, and grew up in a Victorian mansion called Shambellie, near Dumfries in Scotland. The land had been owned by the Stewart family since 1625, with the house built in 1855 by David Bryce, a leading Victorian Scottish architect. “The house was lit by oil lamps and candles… to a small child it seemed a giant’s castle,” Stewart later wrote. “The mysterious upper regions emitted startling creaks and bumps and at times a curious slithering sound.”

-

Shambellie House near Dumfries, Scotland

Image by Flickr user Magnus Hagdorn. Used under CC BY-SA 2.0 licence. Some rights reserved.

-

He was a conscientious objector

During the Second World War, Stewart served as a stretcher-bearer in London. Aged 24, he was posted to the Air Raid Precaution Depot in Battersea, where he lived in (another) huge Victorian house on the edge of Wandsworth Common. During his free time he began to draw – sketching his colleagues and the depot cat. It was also during these months that he first read Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1864 novel, Uncle Silas, the story of a young girl’s imprisonment in a Gothic mansion at the hands of her scheming uncle. Stewart recalled: “The real war seemed curiously remote. In this state of limbo Uncle Silas became a means of withdrawal from the anxieties and disorientation of a life more unreal than the world of the book.” Of his own accord, he began to work on illustrations to the book – which were finally published in the 1980s. These are the works you can see in our Tennant Gallery.

-

Charles Stewart, The cat rejoiced in the name of Adolf!, 1940-42.

Chalk on paper. The cats were drawn at Battersea ARP 1940-42. Private Collection..

-

He was a ballet dancer

In 1932 Stewart enrolled at the Byam Shaw School of Drawing and Painting, and while a student there he discovered an unlikely passion. The newly formed Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo had arrived in London, and Stewart was captivated by its “poetic fusion of dancing, music and theatrical design.” He started taking ballet lessons and by 1936 was performing with the corps de ballet at Covent Garden under Sir Thomas Beecham. The season included a performance of Salome conducted by its composer, Richard Strauss. But Stewart’s conflicting artistic allegiances caused problems. He had been awarded a scholarship to Byam Shaw and its principal, Ernest Jackson, delivered him an ultimatum: he was to choose either drawing or dancing. Consequently, Stewart gave up ballet to continue with his art studies.

-

He collected costumes

Driven by his interest in the theatre, Stewart collected 18th and 19th century costumes. He would scour Portobello Road and Bermondsey markets, and apparently frequented one dealer’s shop in Soho where he had to rummage through trunks in a grimy attic room full of cats.

In 1954, Stewart bought a life-size artist’s model from the 19th century. There are many stories about “Rosie”, as he called her. According to our curator, Amanda-Jane Doran, Rosie was actually the favoured two wooden models – who in Stewart’s mind didn’t get on. Rosie apparently once fell in the stream at Shambellie, having been “pushed” by this other doll. But perhaps her most triumphant moment was when Stewart loaned her to the artist Pietro Annigoni, and for three weeks she stood in for the Queen at Buckingham Palace, dressed in garter robes, whilst Annigoni finished his official portrait of the Monarch.

In 1977, Stewart donated his 2000-strong costume collection to the National Museums of Scotland and in 1982, Shambellie was opened as the National Museum of Costume. Sadly, it has since closed down.

-

Charles Stewart, Rosie, Wearing Day-Dress, c. 1873, 1970.

Watercolour on paper. Private collection. © Estate of the artist.

-

He died in Oxford

Stewart returned to Shambellie in the 1960s to take care of the estate and his invalid father, leaving his life in London and his role as joint principle of the Byam Shaw School. After twenty years in Scotland, he then spent the last years of his life in sheltered housing in Oxford, where Rosie remained with him until he died. Rosie fared rather better, and now lives a finer life in Kensington Palace.

-

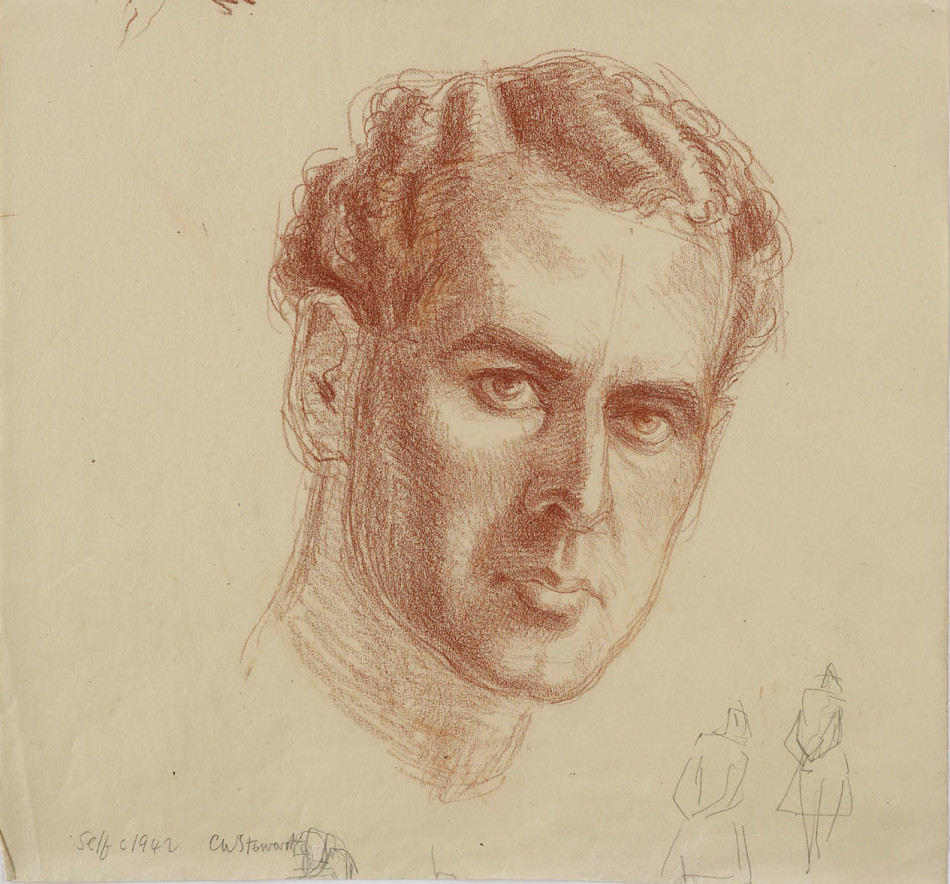

Charles Stewart, Self-portrait, c. 1942.

Private collection. © Estate of the artist.

Chalk on paper.

-

Charles Stewart: Black and White Gothic is in the Tennant Gallery until 15 February 2015.