Travel: on the Bauhaus trail, from Weimar to Berlin

Travel: on the Bauhaus trail, from Weimar to Berlin

By Sam Phillips

Published 28 March 2019

To mark 100 years of the legendary art school, Sam Phillips follows its fortunes from Weimar, via Dessau, to the German capital.

-

From the Spring 2019 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA. This issue is an arts education special, to mark the 250th anniversary of the RA Schools.

-

One of the best destinations on Berlin’s cultural map is the Bauhaus-Archiv, whose objects and images take us back to the 1920s, when the legendary Bauhaus School was in full flow, unifying art and design in new forms that would define the modern world. But in 2019 – the school’s centenary – Bauhaus fans will be rewarded by going further afield. Ahead of the opening of a new Bauhaus museum alongside the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin, dedicated museums are opening in nearby cities Weimar and Dessau, the Bauhaus’s former homes, and there is a wealth to see related to the school’s evolution.

Weimar was a flag-bearer for Renaissance and Enlightenment culture, its rulers patrons of Cranach, Bach, Goethe, Schiller and Liszt. Henry van de Velde is less well known, but the Belgian-born artist and designer was a pivotal figure in laying the ground for the Bauhaus, as Director of Weimar’s School of Arts and Crafts in the early 20th century. Van de Velde had close links with the Deutscher Werkbund association, through which artists, designers, architects and industrialists would collaborate, and he fostered interdisciplinary ideas that became a hallmark of the Bauhaus. It was he who recommended Walter Gropius as his successor – then, in 1919, Gropius merged the city’s art schools to form the Bauhaus in Van de Velde’s Art Nouveau-designed campus.

-

The restored director’s office at the Bauhaus, Weimar (now Bauhaus-Universität Weimar), designed by Walter Gropius in 1923

Bauhaus-Universität Weimar/Photo: Tobias Adam/Walter Gropius, Gertru Arndt, © DACS 2019

-

Today one can tour the buildings of the Bauhaus, Weimar, whose gems include restored murals by Bauhaus masters including Oskar Schlemmer. But the highlight is Gropius’s office (above). Conceived as a cube, the room arranged angular furniture, tube lighting and geometrically patterned weavings – all designed in the school’s workshops – into a visual manifesto for the Bauhaus. The office became a key element of the 1923 exhibition that promoted the school amid attacks from locals wary of its experimentation and, in particular, the mysticism preached by teacher Johannes Itten. The Expressionist painter’s visionary preliminary course and promotion of the Mazdaznan cult brought him a devoted following among the student body. Still standing in the nearby city park are the ruins of the Tempelherrenhaus, an 18th-century folly where Itten had his studio and led students in drum sessions and other practices.

On the other side of the park lies Haus am Horn, a small flat-roofed house designed by another Bauhaus teacher, Georg Muche – the fact that he was a painter attests to the school’s interdiscplinary ethos. Although unstartling to today’s eyes, viewers initially balked at its simple structural design in steel and concrete. Yet the integration of materials, form and function – particularly in the kitchen, where rectangular corner cabinets were set above and below an angular worktop – revolutionised 20th-century domestic interiors. It was built as a model house for the 1923 exhibition, and an entire housing estate was planned. But Weimar was an early stronghold of National Socialism, and the state government became reliant on the Nazi party’s support – funding for the Bauhaus’s progressive work was soon cut, precipitating a move to Dessau in 1925.

Weimar’s Gauforum, its 1930s buildings surrounding a large square, is an exemplar of Nazi architecture, and the new Bauhaus Museum Weimar (pictured top; opening 6 April) has been placed nearby, creating a difficult but important dialogue between the two. From afar the museum is a glowing box, its lit-glass exterior beckoning one into an outstanding collection spotlighting the school’s early work in Weimar.

-

Georg Muche, House Am Horn, 1923

Image courtesy Klassik Stiftung Weimar

-

The new Bauhaus Museum Dessau (opening 8 September) in turn focuses on the school’s golden age after 1925, when it found a home in one of the region’s most important industrial cities. Hugo Junkers was an important local manufacturer who encouraged the liberal mayor to bring the school to the city. The original Bauhaus School in Dessau, designed by Gropius, is a triumph of modernist architecture and is now restored. Huge curtains of glass afford interesting views at every angle onto the structure’s asymmetrically arranged cuboid elements. In recent years the workshops were used as exhibition spaces, but the new museum in Dessau’s central park will take on this role, allowing these airy rooms to breathe once more.

One can stay over at the school, in the staff and students’ digs. Instead of a TV and en-suite, the rooms come complete with copies of chairs by Marcel Breuer, fittings by Marianne Brandt and blankets seemingly straight from the school’s weaving workshop. A 20-minute walk from here is the Kornhaus restaurant, designed by Bauhaus teacher Carl Fieger. Its semi-circular glass fronting affords splendid views of the Elbe.

The school was also involved in the construction of housing in the city. In a small pine forest, Gropius designed Masters’ Houses where Bauhaus teachers lived with their families: Klee and Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy and Lyonel Feininger, Muche and Schlemmer. Inside, each house is arranged around a large studio with diffuse northern light. But by 1932 politics had turned a hard-right in Dessau too, and this merger of art and life was to end, with then director, architect Mies van der Rohe, taking the school to Berlin to live out its final months.

Sam Phillips is Editor of RA Magazine. Visit www.germany.travel for more information on Bauhaus sites.

-

-

Course: Inside the Bauhaus classroom

Ahead of leading an RA course, artist Fritz Horstman spotlights a work made under the guidance of Bauhaus master Josef Albers.

Material Studies, or Materie, were at the very heart of the Bauhaus – not only of its Preliminary Course, but of its entire curriculum of experimentation and learning- by-doing. The focus instructors placed on mundane materials changed the course of modern art and design education. Where previous pedagogies had taught that the most advanced students would work with precious materials such as marble, Bauhaus students were encouraged to investigate the humblest of materials such as wire, thread and newspaper.

Josef Albers arrived at the Bauhaus in 1920 as a student. His proficiency was quickly identified and he was asked to teach a section of the Preliminary Course in 1923. By 1928 he was running it. Albers saw the value of putting basic materials into the hands of students. With simple hand tools and intuition, students developed a deep understanding of the potential and limitations of their materials. Instead of memorising established design principles, they discovered their own. Improvisation was celebrated.

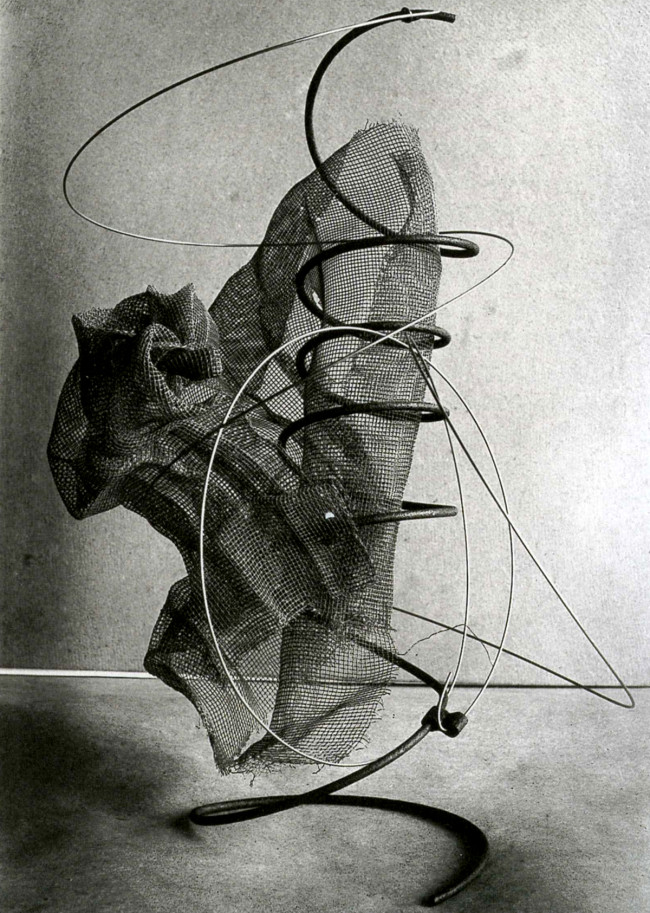

This year, to mark the school’s centenary, a five-day practical course at the Royal Academy explores the exercises led by Albers, as well as other influential Bauhaus masters such as László Moholy-Nagy. While creating Materies, Albers’ students were guided to seek the essence of their chosen material both in isolation and in combination. In a photograph from Albers’ class (pictured) we see a student’s project of coiled and looping wire combined with wire mesh. Two gauges of wire have been used. The stouter of the two is spiralled almost as a spring, and exhibits its structural strength by carrying the weight of the entire assemblage. The thinner wire is attached at top and bottom by small clips, and still looks ready to spring loose at the slightest jostling.

The wire mesh most readily exhibits the thinking hand of the student. Loosely rolled into the larger wire’s coil at the centre of the photo, on the left it is twisted and scrunched in a way that demonstrates the flexibility and memory of its constituent metal. There are no classical compositional techniques evident in this assemblage, yet the student has found a way of showing the capabilities and limitations of its materials, as well as the process of making it. The core tenets of Bauhaus pedagogy are beautifully demonstrated in its most quotidian of materials.

Fritz Horstman is Artist Residency and Education Coordinator of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. He leads the course The Bauhaus Preliminary Course: Light and Space and Thread 22–26 July. Image courtesy the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

-