When Morris met Warhol

When Morris met Warhol

By Jeremy Deller

Published 5 December 2014

The Arts and Crafts pioneer and the American Pop artist may seem an unlikely pairing, but artist Jeremy Deller draws out some intriguing links ahead of his show at Modern Art Oxford.

-

When I tell people I am curating an exhibition that pairs William Morris with Andy Warhol, the reaction is often one of puzzlement. The two artists never met, nor did they share the same century, and their political views could be seen as diametrically opposed. On the face of it, this show seems an odd idea. But visit Modern Art Oxford this winter, and it will become clear that Morris and Warhol have much in common.

Both artists came from – and turned their backs on – the industrial culture of the times. Morris’s family wealth came from his father’s investment in lead mines in Cornwall. Warhol, however, came from the other end of the spectrum, having lived in the very working-class environment of the steel town of Pittsburgh. Like Morris, Warhol lost his father as a teenager – he suffered a terrible, long-drawn-out death, probably through accidentally drinking poisoned water at work.

Both artists were deeply imaginative as children. Morris was obsessed with the romance and fantasy of knights in a medieval age, to the point where he even had his own suit of armour. He was a sickly child and his schooling at Marlborough College was not a happy one, so to distract himself he would roam the ancient countryside nearby, which was filled (as it still is) with Neolithic monuments.

Warhol too was unwell for a large part of his childhood and as a result spent much of his time at home with his mother where he would write to film stars and obsessively collect their autographs in scrapbooks. Both artists immersed themselves in mythology – Morris in that of Ancient Britain, Warhol in that of Hollywood. These interests informed their careers to the end, and they are the starting point of my show.

-

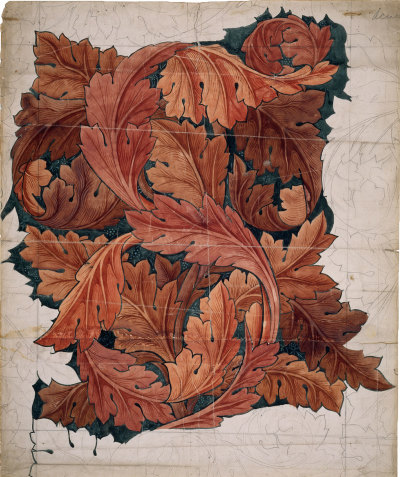

'Acanthus', 1879-81, a wallpaper design by william morris

Andy Warhol, Flowers, 1970.

-

Morris’s obsession with the medieval reached its pictorial height in the 1890s with the ‘Holy Grail’ tapestry series, which took him five years to make, and I have borrowed the climactic panel depicting the attainment of the grail, which I have hung opposite Warhol’s mythological characters of 20th-century America. The Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh has loaned us a lot of material, including a signed, hand-coloured photo of Shirley Temple (Warhol’s favourite star). This photo more or less became the template for every subsequent female portrait he made.

There is also a room that I’ve called ‘Flower Power’, which examines decoration, repetition and nature. Flowers were a favourite subject for Warhol, and Morris’s floral designs articulate his belief in the harmony of nature and desire for society to reflect this ideal. The show has six of Morris’s large watercolour designs for fabrics and wallpapers, including Acanthus (above left) – works of such incredible beauty that they must be seen to be believed. Warhol’s ‘Flower’ series (above right) from the 1960s and ’70s is shown alongside.

Throughout their lives both artists tried to reinvent the notion of the workplace by shaping it towards their idealised visions of the world. For Morris it was a place where work was fulfilling, skilled and life-enhancing; for Warhol a place of glamour, random encounters and hard work. Morris was, after all, an artist who owned a shop with his name on the entrance, and Warhol built his iconic art Factory, and by doing so both made their brands stronger. It is clear they were fascinated with the intersection of art and design, the point where high art and commercial art met, and how that enabled their art to be widely consumed.

As Morris once said: ‘I think it is desirable that the artist and what is technically known as the designer should practically be one.’

Love is Enough: William Morris & Andy Warhol curated by Jeremy Deller is at Modern Art Oxford from 6 December – 8 March 2015, then Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, April–August 2015.

Jeremy Deller is an artist. Jeremy Deller: English Magic is on show at the Turner Contemporary, Margate, until 11 January 2015.