Linton Kwesi Johnson on poetry as an act of resistance

Linton Kwesi Johnson on poetry as an act of resistance

By Caleb Azumah Nelson

Published 30 November 2021

Yinka Shonibare RA invited the renowned Brixton-based reggae poet Linton Kwesi Johnson to bring his powerful words to the Summer Exhibition. Caleb Azumah Nelson sits down with him to discuss the poetry of resistance.

-

From the Winter 2021 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Caleb Azumah Nelson is a photographer and writer. His first novel Open Water (Viking) was published earlier this year.

“Where are you from?” Linton Kwesi Johnson asks me. When I tell him I was born in south London, but my parents are from Ghana, he leans back in his seat and smiles. Within moments, the poet has explained the origin of his pen name (Kwesi is the name given to men born in Ghana on a Sunday), as well as Anansi the Spider, a folklore hero in many West African and Caribbean households, and the way that language in Jamaica is influenced by Ga, a dialect in Ghana, which he supposes is a residue of culture in the wake of colonial rule. For him, reflecting on where we and others are from is not about division but a starting point for community. When he’s asking where we’re from, he’s asking who we might be, what might be possible for us as children of the diaspora.

We meet at the Ritzy Cinema, in Brixton, where as a child Johnson would be taken to the Saturday afternoon pictures. Next door is Brixton Library, where, after being awarded the C. Day Lewis Fellowship in 1977, he was a writer in residence. Though Johnson was born in Clarendon, Jamaica, he moved to Brixton in 1963, and it has been home since. It felt like home too; in the face of racial hostility in the area, local people, mostly Windrush settlers, doubled down on their culture as a means of reaffirming their identity, ensuring the community had access to food from the Caribbean, opening record shops, barber shops for men, hair salons for women.

-

Linton Kwesi Johnson

Caleb Azumah Nelson

-

“There were huge barriers put up against us,” Johnson says. “We came here to make a life, to work, to let our children go to school, but it wasn’t easy.” In addition to what he refers to as “the colour bar”, a systemic barrier preventing Black people from thriving at the time, the police were waging war on the community, in ways both violent and insidious. These cultural markers – the food, the music, the space – were no longer just that. They were protest, resistance.

Poetry was part of this resistance. After reading The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois, an experience he describes as a “spiritual awakening”, he began to write. He always saw poetry as a weapon in the Black liberation movement, a way to raise consciousness, give spiritual nourishment, lift morale. His work chronicled the experience of Black people in the UK, giving expression to the sentiments of the youth, and it was often set to dub rhythms, the rhythms of his people. Early on, he was involved in the Caribbean Artists Movement – founded by Kamau Brathwaite, John La Rose (of New Beacon Books) and Andrew Salkey – a space which encouraged the “teasing of their own autonomous aesthetic, rather than seeking validation from the gatekeepers”, leading to a revival of orality, the work steeped in “what we grew up in”.

-

There were huge barriers put up against us, we came here to make a life, to work, to let our children go to school, but it wasn’t easy.

Linton Kwesi Johnson

-

This space encouraged the carving of a line, the forging of his craft, influenced by poets such as Christopher Okigbo, a Nigerian poet who wrote in English steeped in Igbo rhythms; Léopold Senghor and Aimé Césaire, who were both foundational to the Négritude movement; and Tchicaya U Tam’si, a surrealist poet from Congo. Music, too: James Brown (Johnson cites ’Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud’ as a direct influence); The Last Poets, who used African- American vernacular as a vehicle for the spoken word; reggae DJs, such as Big Youth; and the drummer Count Ossie.

It’s only right then, that he is part of the RA Summer Exhibition, whose co-ordinator Yinka Shonibare RA has encouraged African diaspora artists to sit at the heart of the show. Invited to contribute to the sound programme, Johnson chose to read a piece titled ‘Di Great Insohreckshan’ (1984), which speaks to the events of the Brixton uprising in 1981. The poem itself is a marvel, a quietly powerful display of mastery of craft, combined with the deep expression of self. In a deep, sonorous voice, he speaks to what it might have meant to be him at that time, what it might mean to have to speak towards your freedom.

-

Linton Kwesi Johnson

Caleb Azumah Nelson

-

This isn’t, however, his first foray into the art world. While working as the arts and poetry editor at Race Today, first edited by Darcus Howe, Johnson created a smaller offshoot organisation known as ‘Creation for Liberation’, with the aim of providing a platform for art in tune with the struggle for racial justice. A show organised by Johnson, held in Brixton’s St Matthew’s Church as well as a space on Atlantic Road, served as the first open exhibition for Black artists, showcasing work by Keith Piper, Eddie Chambers and Sonia Boyce RA. Though contemporary art was not his medium of choice, Johnson says, “I knew what I liked, knew what moved me”.

As he speaks, a dub bassline rattles out from the speaker. Johnson’s eyes flicker in that direction, a clear attraction present. I follow this path, asking him about this process, of collecting sound. He’s quick to smile again, and with a wave of the hand, almost conceding, says, “It’s all over the place! A line here, a phrase here, a walk in the park to get the mind going… I’ll get an idea, or be moved by something, maybe an image, and a phrase might suggest itself in a particular rhythm. Then I’ll build on that.” A poem, he says, might be like hundreds of pieces of paper, stuff scribbled down, scattered until he finds order in the chaos. This, I think, is where Johnson’s power lies: in the ability to be led by his heart, his intuition, to submit to his own feelings and ideas. It’s the music, he says, which allows this. The tension between the language of music and the music of language is where his aesthetic lies. In particular, the bass guitar – on which he tries to model his own sound architecture – an instrument which I believe builds space where a deep expression might be possible, in the lowering of frequencies, where time feels like it slows. As we talk, the music shifts. Another dub rhythm. Johnson smiles once more, his attention elsewhere, to the music, to the rhythm, to the space the bass makes, which like his earlier question, speaks not just to where we are, or where we have come from, but to what might be possible.

The Summer Exhibition 2021 is open until 2 January 2022. You can listen to Linton Kwesi Johnson’s poem as part of the Summer Exhibition Sound Programme here.

-

-

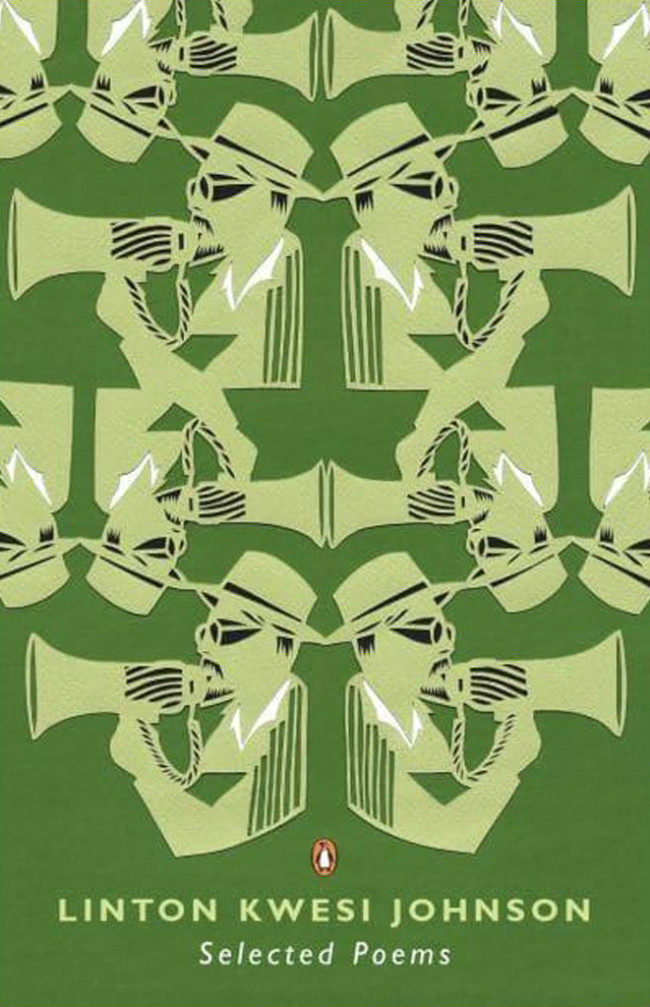

Buy Linton Kwesi Johnson's 'Selected Poems' from the RA Shop now

A selection of Linton Kwesi Johnson’s best poems over three decades. Ranging from protests against police brutality to eulogies for departed friends and playful celebrations of urban life, Johnson’s use of Jamaican dialect to tackle distinctly British subjects contributed to a revolution in the notion of literary English. This Selected Poems charts the unique literary talent of one of Britain’s most influential poets and social critics.

This book is part of a curated reading list by Yinka Shonibare CBE RA, created especially for the RA Shop.

-

-

Learn more about the Summer Exhibition 2021 sound programme

Pelin Pelin is another of the artists who created an exclusive track for the show, and here she explains her intention to take listeners on a sonic journey with ‘Torch of Time’.

-

-

Enjoyed this article?

Become a Friend to receive RA Magazine

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

-