Woodwork: how does it work?

Woodwork: how does it work?

By Fiona Maddocks

Published 29 April 2020

The centuries-old techniques of woodcut and wood engraving are alive and well today, holding an enduring appeal for contemporary artists. But what are these processes and what is the difference? Fiona Maddocks investigates.

-

Adapted from the Spring 2020 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA. Please note: this article was created to coincide with the London Original Print Fair held annually at the RA, which unfortunately has been cancelled due to the ongoing circumstances surrounding coronavirus. Instead the fair will be online from 1 May.

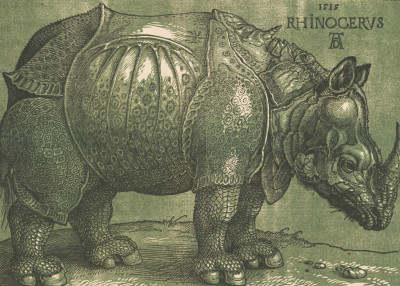

Images that are printed using wood: what springs to mind? Dürer, Munch or the German Expressionists? Traditional Japanese prints or illustrations in a beloved children’s book? The natural, hand-made feel of a woodcut, where the pattern of the wood’s grain might alternate with the deepest of ink-drenched tones, can be immediately identified. Yet the terminology is a minefield, and the techniques and materials – wood engraving, woodcut, woodblock (the East Asian woodcut tradition), end grain, long grain – as rich and varied as wood itself. Wood engravings, which use the finest-grained blocks of wood, can be as small as postage stamps, whereas woodcuts can be as large as an assembly of planks.To find out more, I watched two artists at work on woodcuts, in preparation for the London Original Print Fair at the RA: one, the sculptor Frances Richardson, a newcomer to the form, working with a master printmaker; the other, Tom Hammick, a woodcut printmaker of long experience, in his studio. I also sought the guidance of the Royal Academy’s leading wood engraver, Anne Desmet RA, a distinguished practitioner in this increasingly popular medium, who has curated an exhibition on the discipline at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, opening this spring.

“Wood engraving is done with fine-tipped tools originally developed for the metal engraving trade,” explained Desmet, when I asked her about the distinction between wood engravings and woodcuts. She described how these tools enable intricate images to be hand-carved, specifically on end-grain wood – the short cross-sections produced when one cuts laterally across a tree’s growth rings. End-grain, from certain very slow-growing trees, has a tightness that allows highly detailed working. “Woodcuts, in contrast, involve working with the long grain of a tree, cut longitudinally, so they can be much bigger. The tools are U- and V-shaped gouges – or special Japanese cutting knives – used to carve either with or against the direction of the grain, which itself often becomes part of the image. In the historic Japanese woodblocks of, say, Hiroshige, you can often detect the grain in the beautiful skies.”

-

Blocks of end-grain wood, with some engraved by Anne Desmet RA

Photo: Tom Willingham

-

How to make a wood engraving

Artist Anne Desmet RA demonstrates the centuries-old technique of wood engraving as she creates her limited-edition print San Severino Marche.

-

My first stop to see how woodcuts are made today was Paupers Press in Hoxton, London, set up by Simon Marsh and Michael Taylor in 1986. This fine-art print and publishing studio collaborates with many leading artists, among them Damien Hirst, Paula Rego RA and Tracey Emin RA. On the day of our visit, two of the Paupers team were working on a big woodcut by Grayson Perry RA. They inked up large pieces of wood – laser-cut from a digital file sent by the artist – one colour at a time, then fitted them in place like a jigsaw, before pressing, rolling and smoothing with wooden spoons to make the imprint and build up the picture on paper. The sculptor Frances Richardson was there with Taylor, ready to experiment with her first woodcut print with his expert help.“You have to think in reverse…” Taylor explained patiently, although not entirely helpfully for the uninitiated. He was going back to basics, reminding me that any incised print, in whatever medium, is a mirror image of the original. “It’s all about the relationship between the material and the image. So many variables feed into every decision an artist will make.” He listed them: wood, ink, volume of ink, the mark, the pressure, the paper. “If you want a tight grain for engraving, you might use the end grain of, say, a pear tree. If you’re doing woodcutting, you would go for long grain, maybe oak or pine. A lot of artists use old shutters they’ve picked up from skips. As for tools, a router is good for broader marks, as it gives a more crude quality, which can be very satisfying, whereas a laser cut will give you finer, cleaner marks.”

Richardson brought small, rectangular samples of Maple Cluster burr veneer, which is thin and malleable as parchment, with a grain as elaborate as marbled paper. She had used this same material in an assemblage of cylindrical sculptures entitled Not all temporary objects can be avoided (2018; below left). Early in her career, she spent time in Nigeria and learnt the traditional Yoruba style of wood-carving. “I could have just sent Mike an image to reproduce,” she explained. “But I am really interested in the nature of the materials I use. Could I create an image that’s in tune with, or appropriate to, my current work? Why do a woodcut? That’s what fascinates me.” For the next two hours, sculptor and printer worked together, sampling tools (top left), colours, rollers and, finally, Paupers’ Victorian printing press (centre left). Part of Taylor’s skill was to understand precisely how to interpret Richardson’s intentions, showing her how to ink up a block; how to make a soft edge or achieve a speckling effect; above all how to enjoy the balance of randomness and control which makes this such a dynamic art form. She explored abstract, gouged strokes, as well as a naturalistic landscape. “You have to hand over some of your autonomy,” she said, “but Mike has helped me see the potential of the medium, and the subtle and dramatic effects that can be produced in the conjunction of ink, wood, paper and method of printing – and how I could adapt the process for my own practice.” A limited edition is often the result of several meetings between artist and printmaker; at the end of this exploratory session, Richardson and Taylor arranged a date for the following month, to work further towards the final print.

-

Frances Richardson and master-printmaker Mike Taylor at Paupers Press

Photo: Thom Atkinson

-

Frances Richardson, Not all temporary objects can be avoided, 2018.

© Frances Richardson.

-

It’s all about the relationship between the material and the image. So many variables feed into every decision an artist will make.

Michael Taylor

-

South of the river in Bermondsey, Tom Hammick creates monumental but tender multi-colour images using several kinds of print and painting techniques, but with wood as a constant. Wearing a big apron, he resembled an inventive chef who creates culinary fantasies from an adored single ingredient. Large stencils lay on the studio floor, some forming the relief for a print. Others provided a shape to imprint on another surface, to be painted or worked over in some way. As an associate artist at this year’s Glyndebourne Festival, he was making pictures inspired by the six operas being staged this season.

Hammick’s pictures, drawing from sources as diverse as Japanese woodblocks to Northern European romantic painting and contemporary cinema, tell stories: from family life, newspaper cuttings, poems, opera plots. Forests, trees, sky, moon and night feature in what he calls the “imaginary and mythological dreamscape” of his work. His Lunar Voyage (2017), a suite of 17 woodcuts, depicts what he calls a “lonely dystopian journey to the Moon and back”. He may start with a drawing or painting, work it up in wood, transfer it to paper, paint it, apply collage, or alter it in any mood or manner or media that suits the moment. “The painting feeds the prints, the prints the painting. I often paint a picture at the same time that I’m making it in wood. It’s all part of the prep.”

-

Tom Hammick, Night and Day, 2019.

reduction woodcut triptych. ©Tom Hammick, all rights reserved Bridgeman Images.

-

Colour woodcuts tend to be printed from separate blocks, one for each colour. Unusually, Hammick makes reduction woodcuts. Colours are all printed from one block, each colour in succession (usually light to dark), as the original surface of the block is cut away, or reduced. “In a funny sense you have less control, when you’re carving away to print over a previous layer, because once you’ve removed an area of wood, there is no going back,” he said. “It becomes a seat-of-your-pants process, where you’re constantly taken by surprise. I have an idea of where I’m aiming at the start, but I don’t really know where it’s going to end up. I like that risk, that wriggle room. It’s like driving an old-fashioned Land Rover where you have to yank the wheel round in response to what’s happening on the road.” Printmaking can be quite prescriptive, but not in Hammick’s case. “When I make an edition, each of the prints will be slightly different.” As an example, he demonstrated – with the help of his studio team, which includes his sister and his niece – how a round piece of wood, to depict the moon, could be scored and inked up differently with each imprint, achieving subtle differences each time: now bluey, now grey-green, more pitted or pocked. He uses a Polymetaal etching press, made to his specification in Holland. “No motor! Just a large, hand-turned wheel.” Hammick’s work itself almost turns full circle: in his images of coppiced trees, lonely woods, verdant gardens, his prime material becomes his subject. The Dark Woods of England – Explorations of Love and Loss (2019), in an edition of 15, shows a family about to disappear into the forest, like Hansel and Gretel. The use of wood, and its complex language of grain and texture, reflects Hammick’s kinship with, as well as fear of, the enormity of the natural world. “When you cut a piece of wood, that mark holds its own authority,” Hammick summed up. “And the wonderful thing is that accidents happen. That’s what I love about working in wood: the infinite mix of freedom and constraint.”

-

-

Enjoyed this article?

Become a Friend to receive RA Magazine

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

-