Meet the artist: Marianne Werefkin

Meet the artist: Marianne Werefkin

By Francesca Wade

Published 10 October 2022

A dynamic influence in artistic circles, the Russian-born painter devised a haunting idiosyncratic style of her own

-

From the Autumn 2022 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Francesca Wade is the author of Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars (Faber). She is working on a book about Gertrude Stein.

Marianne Werefkin’s paintings often include small, hunched figures in dark clothes, struggling down long roads, laden with babies or laundry bags, sharing rueful moments of solidarity with others or lost in solitary contemplation. Yet her circus scenes and portraits of dancers display her fascination with the full range of human experience: her work is united by a distinctive attention to moods, emotions and the movement of the human body, whether contorted in suffering or driven by the fervour of performance.

Werefkin was born near Moscow in 1860 into an aristocratic Russian family, and studied in several cities around the Russian Empire as her father’s military career necessitated frequent travel. In 1888, Werefkin accidentally shot her own hand during a hunt, and had to re-train herself to paint; a period of medical treatment in Germany occasioned her first immersion in Western European art through the country’s museums. A daily ritual visit to a portrait of Alessandro del Borro, attributed to Diego Velázquez and held in Berlin’s Staatliche Museen, stirred in Werefkin an urge to pursue art full-time on her recovery: admiring its subtle use of shadow and grand style, she wrote to a friend five years later, “I started to want to live again, to see it again and again, to live on by painting and perhaps by painting alone.”

-

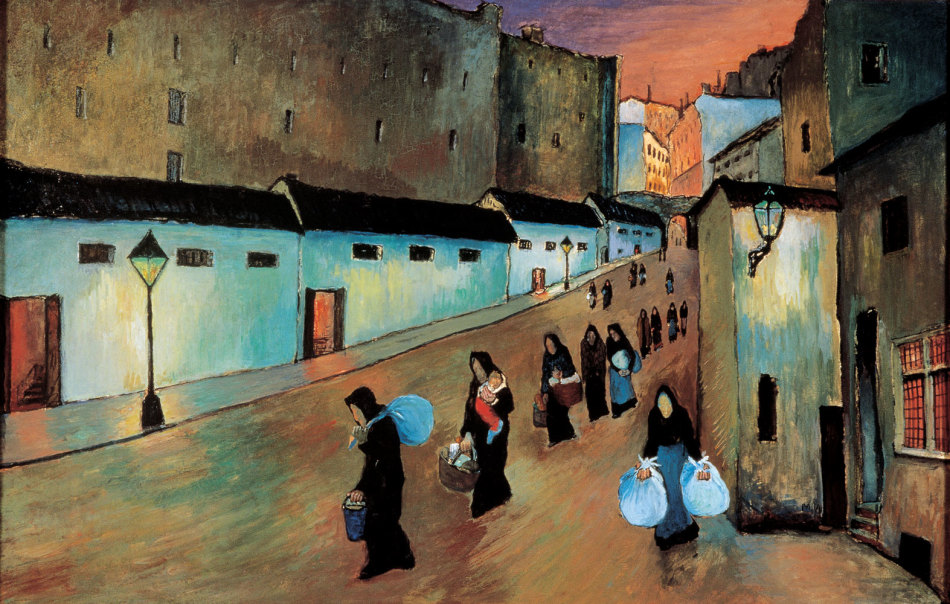

Marianne Werefkin, The Return, 1909.

Tempera on paper on cardboard. 52 x 80.5 cm. Ascona, Museo Comunale D’Arte Moderna.

-

In the 1880s, Werefkin studied with the renowned Russian artist Ilya Repin, who compared her to Rembrandt and was convinced she had the talent to become a great realist painter. But this was not Werefkin’s plan. In 1892 she fell in love with another of Repin’s students, Alexei Jawlensky, and the pair became the centre of a lively group of international avant-garde artists, who pored over prints of renowned European artworks and eagerly discussed new techniques and ideas picked up from the latest books and magazines. In 1896, Werefkin and Jawlensky moved to Munich, where Werefkin confidently took charge of managing the household, and of doing all she could to enable Jawlensky’s art through her connections, money and emotional support. During the next decade, Werefkin’s own painting production ceased, as she rethought, through works on paper and writing, the tradition she had mastered alongside Repin. Travelling widely across Europe studying modern and Renaissance painting, she became determined to incorporate new theories and influences into her own idiom, to collaborate with others who had embarked on similar projects (including the Blue Rider and the NKVM, of which she was a founding member), and to show her work internationally through the wide network she had established at her famed salons, which were frequented by artists including Wassily Kandinsky.

-

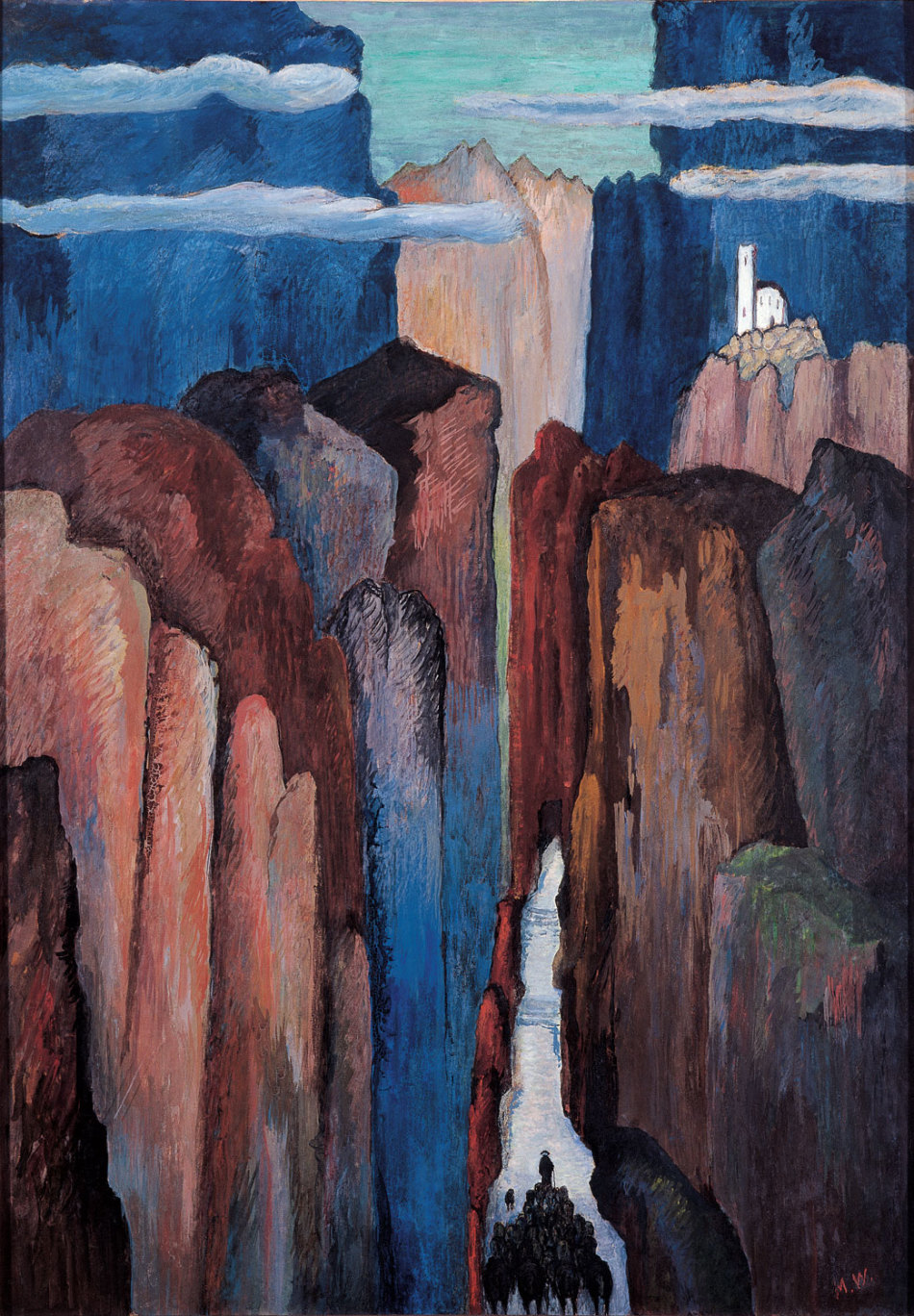

Marianne Werefkin, Eternal Path, 1929.

Tempera on paper on cardboard. 100 x 70 cm. Collection of the Municipality of Ascona, Museo Comunale d'Arte Moderna, Ascona.

-

When she did return to painting in 1906, aged 46, Werefkin’s approach to the medium had revolutionised. Her exposure to Symbolism and Fauvism in France – in particular the work of Gauguin, Matisse and Derain – had set her mind alight with new ideas. Her work was shown in several significant exhibitions, including the radical Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne in 1912, and at Herwarth Walden’s influential Galerie Der Sturm in 1914 (where her art appeared alongside that of the Dutch painter Jacoba van Heemskerck, another artist in the Royal Academy show).

For Werefkin, the quality of a painting was commensurate with the sincerity of the painter’s emotions. “Being an artist,” she wrote, “does not mean possessing a faculty of combining lines and paints… but having a world inside oneself and individual forms to express it.” She wanted her work to convey the rhythm of movement; many of her paintings feature long roads, rising across the canvas as in The Return (1909), which shows a parade of hooded figures processing down a lamplit boulevard. Their purpose is mysterious, yet Werefkin perfectly captures the effort of their long trudge, lifted by the glorious sunset behind them.

She spent her later years in Switzerland, focused on the landscape of Ascona, on Lake Maggiore: many of her late works explore the textures and colours of the mountains, engulfing her human figures in a fantastical natural world. The walker in Eternal Path (1929) is as tiny as the house on the mountaintop that might be his eventual destination; Werefkin’s vertiginous experiments with perspective express her abiding spiritual concern with human fragility and resilience.

-

Marianne Werefkin, Twins, 1909.

Tempera on paper. 27.5 x 36.5 cm. Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale d'Arte Moderna, Ascona.

-

Making Modernism: Paula Modherson-Becker, Käthe Kollowitz, Gabriele Münter and Marianne Werefkin The Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries, Royal Academy of Arts, 12 Nov-Feb 2023. Supported by BNP Paribas with additional support from the Huo Family Foundation, The Tavolozza Foundation, and the International Music and Art Foundation.

-

-

Enjoyed this article?

Become a Friend to receive RA Magazine

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

-