Eileen Gray: an architect and designer you should know

Eileen Gray: an architect and designer you should know

By Michelle Doyle

Published 2 March 2021

A designer of decorative furniture and Modernist architecture, Eileen Gray found recognition aged 94. As part of our International Women’s Day programme, here’s our guide to the life of this overlooked master, and her infamous seaside villa, E-1027.

-

It’s a story as old as art history – a woman, ingenious and indefatigable, produces groundbreaking work while eluding critical attention for her entire career. Eileen Gray’s story, at least, has a happy ending: her unique creative force was recognised in her lifetime – if only just and decades too late.

Eileen Gray was a pioneer who carved out her space in the hostile, male-centric world of Modernism. After finding success as a furniture designer, she turned to architecture and with no formal training, created an iconic building that reinstated warmth and comfort as principle tenets of Modernist design. She found acclaim at the age of 94, before passing away aged 98, in 1976.

How did Gray evade critical attention for so long? Women were largely absent from the Parisian decorative arts scene where Gray was working as a young designer – and she was also deeply shy, and uncomfortable with self-promotion. As Gray put it: “I was not a pusher and maybe that’s the reason I did not get the place I should have had.”

Here’s what you need to know about the life and work of Eileen Gray.

-

-

1. She wasn’t always Eileen Gray

Eileen Gray was born Kathleen Eileen Moray. Born into an aristocratic Irish family in 1878, she grew up in Brownswood, County Wexford, and divided her time between Ireland and London. In 1893, Eileen’s mother inherited a peerage from a Scottish uncle, claiming her title as Baroness Gray. From then on, Eileen and her siblings became known as the Grays.

-

-

-

2. She was one of the first women to study at the Slade

Gray took her place at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1898 where she studied drawing and painting. Her father, James McLaren Smith, was a landscape painter, so fine art probably seemed like a viable and familiar career option.

Gray’s studies ultimately didn’t hold her attention but something else caught her eye during those years. During trips to the Victoria and Albert Museum near her home in Kensington, Gray discovered Japanese and East-Asian lacquerware – objects and furniture decoratively covered with lacquer, the sap of a tree native to Japan.

-

-

-

3. She fused Japanese lacquerwork with geometry

Gray moved to Paris in 1902 where she studied drawing at the Academie Julian – but once again, didn’t enjoy it. By 1906, she’d made up her mind to focus on screens and panels instead (something “useful”, as she saw it). She sought out the Japanese lacquer master, Seizo Sugawara, who agreed to train her in the technique. Gray immediately committed herself to the craft, taking particular interest in red Negoro lacquer – an elegant, minimalist style dating back to the 12th century – which she mixed with maki-e, a technique of sprinkling lacquer on the work and dusting it with decorative powder to make the design.

Gray’s early works from this period often feature figurative details (people, animals) that owed to the symbolist movement, but she later created glossy screens that fused traditional Japanese craftsmanship with the abstract geometric principles of De Stijl, a Dutch art movement active after the first world war. These pared-back pieces with their thoughtful contemplation on form and material quickly brought her work to the attention of the Paris avant-garde.

-

-

-

4. She worked in her bathroom

Lacquering is an extremely difficult technique that requires humid, dust-free conditions and 20 coats of carefully mixed resin – which take two, three or even four days to dry.

Japanese craftspeople traditionally made their lacquerwares at sea for the humidity, so Gray opted for the next best thing – her bathroom.

Meanwhile, alongside her lacquer screens and cabinets, Gray also experimented with fabric and carpet design, and in 1910, she also set up her own weaving studio.

-

-

-

5. She was a businesswoman

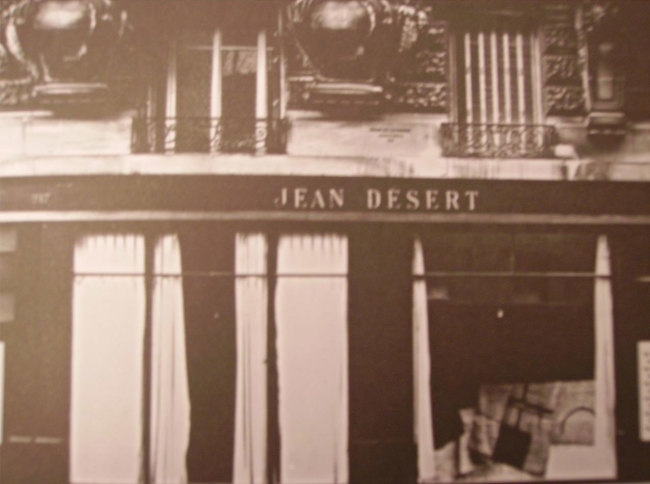

By the early 1920s, Gray had quickly established herself as one of the leading designers of lacquer furniture in Paris, and her next step was to open a shop – Galerie Jean Désert.

Opening a shop in postwar Paris wasn’t unusual in itself; what was unusual was having a woman in charge. Perhaps this explains why she gave her store a man’s name (Jean) and why her business cards read “Jean Désert et E: Gray” – both masking her gender and creating ambiguity around the store’s management.

Gray designed the store in collaboration with the architectural critic and editor, Jean Badovici, with whom she had a romantic relationship and collaborated with professionally between 1926 and 1931. Badovici’s relationship with Gray was the catalyst behind her transition into architecture. Within a few years of opening Jean Désert, Gray had left her shop behind.

-

-

-

6. She became an architect in her late 40s

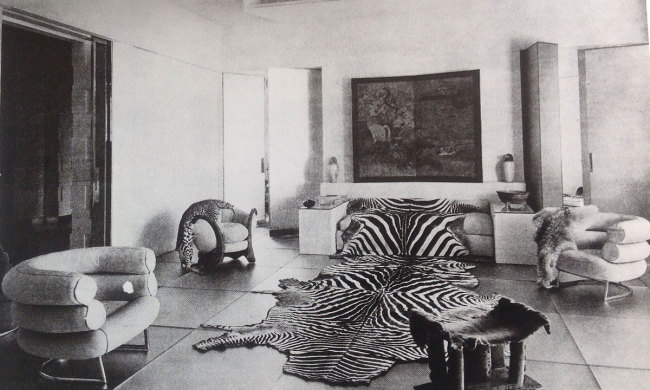

At first, architecture was an escape. The shop was taxing and Gray sketched architectural plans to take her mind off things. She was in her late 40s by the time she formally transitioned to architecture – but she’d been cutting her teeth with chic interiors like that of the Rue de Lotta apartment in Paris (1917–1921) commissioned by Madame Mathieu-Lévy.

Here, she drew upon the ideas of the Deutsch Werkstätten, looking beyond individual items of furniture and focusing instead on holistic, integrated interior design. It was around this time that Badovici began encouraging Gray’s career transition.

-

-

-

7. She designed an iconic villa, with no architectural training

Eileen Gray’s first building resulted in her best-known work, E-1027. It’s a seaside villa in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in France which she completed in 1929 when she was 51. The name of the house is a coded message spelling out her and Badovici’s initials – E for Eileen, then the numbers 10, 2 and 7 which referred to the alphabetical order of the letters J, B and G.

Unlike other Modernist homes, E-1027 mixed moving screens with fixed walls and introduced furniture that could be adjusted and tilted. The bedside table – now one of Gray’s most reproduced designs – could be pivoted and its height easily changed. Her reason? She wanted guests to eat toast in bed without worrying about getting crumbs in the sheets.

-

-

I was not a pusher and maybe that’s the reason I did not get the place I should have had.

Eileen Gray

-

-

The way in which Gray approached the house – with its focus on architecture, adaptable furnishings and their dual role in creating spaces that address each individual’s changing needs – was totally unprecedented in 1929.

The house also highlighted the couple’s interest in French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier – the open plan and raised columns echoing Le Corbusier’s manifesto, Five Points of Architecture. But remarkably, as Gray had no formal training as an architect, she managed to infuse his five-point theory with warmth and comfort, making it both adaptable and highly liveable.

-

-

-

8. Her work was vandalised by Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier was a frequent visitor to E-1027; he built a cabin on the rocks nearby, which is where he drowned in 1965. There’s evidence to suggest he admired Gray’s work – he included her project, Centre des Vacances, at the Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux in 1937 – but he was also allegedly furious that she had used “his style” at E-1027.

Ten years after E-1027’s completion, Le Corbusier defaced the walls of the house with lurid cubist murals. As Le Corbusier said: “I admit the mural is not to enhance the wall, but on the contrary, a means to violently destroy [it]”.

-

-

-

9. Gray completed two more houses – but designed nearly 50

Gray designed Tempe à Pailla at a nearby town called Menton, followed by a home she designed for herself in St Tropez. Her archive holds sketches and drawings for 45 architectural projects that were never realised. She didn’t produce another building for the rest of her life, and produced very little furniture.

As for E-1027 – the designer’s undisputed gem – it fell into disrepair. The Nazis used it for target practice; an artist defaced its walls further by adding a swastika to one of Corbusier’s murals (according to him, it had always been there); and its exposed position meant that it took a battering from the wind and sea.

The house also changed hands after Badovici’s death and by the 1980s, it was rumoured that E-1027 had become a drug and orgy den. Then, in 1996, the owner was violently murdered in the living room and after that, the house rapidly deteriorated. Official efforts to save and restore E-1027 didn’t begin until 1999.

-

-

-

10. Gray found fame at age 94

History almost forgot Eileen Gray who was more or less living in isolation by the time she was rediscovered. It was in 1972 – when Gray was 94 years-old – that she was first “introduced” to British audiences, by the art historian Joseph Rykwert. Writing in Architectural Review, he praised Gray’s “inventiveness” and “visionary intuition.”

A year later in 1973, Zeev Aram of the Aram furniture store asked Gray whether he could reproduce her designs. “In her very quiet voice… she kept asking, ‘Do you think it’s worthwhile to do?‘”, Aram told the Guardian in 2015. The answer, of course, was yes – Aram still sells her furniture today – and the pair worked together until Gray’s death, aged 98.

Today, Eileen Gray is getting the attention she deserves: with exhibitions in Paris and New York over recent years, her furniture now sells for millions at auction. Her work is now a source of inspiration for artists, designers and architects around the world. Among them, artist Eilis O‘Connell created six sculptural works for the garden in 2018, each one responding to Gray’s ingenious use of material and her love of metal.

As for E-1027, the house was restored following decades of neglect and opened to the public in 2015.

-