How to read it: John Gibson’s Cupid and Psyche

How to read it: John Gibson’s Cupid and Psyche

RA Collections

By Annette Wickham and Anna Frasca-Rath

Published 9 September 2016

Take a closer look at how one of Britain’s most celebrated 19th-century sculptors tackled an ancient Roman tale in marble.

-

What’s the story?

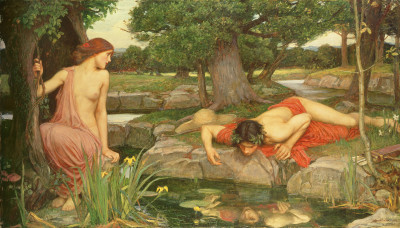

Made in Rome by John Gibson in 1853, this marble tells the story of Cupid and Psyche, an ancient tale from a Roman text The Golden Ass by Apuleius. The story follows Psyche, who represents the soul, as she is sent to live with Cupid – but only ever meets him at night and is never allowed to look at him. One night, she shines a light on him while he sleeps and is so surprised to see the god of Love that she pricks herself on one of his arrows. He flees and the lovestruck Psyche embarks on a journey to find and eventually marry him, overcoming the many obstacles put in her path by Cupid’s mother, the goddess Venus.

So what exactly can we see here?

In the scene Gibson has chosen here, it is Cupid who is pursuing Psyche – so we think this episode represents the end of the story, where Venus sends Psyche to the Underworld to ask its goddess, Proserpina, for a box containing the essence of beauty. On her way back, Psyche gives into curiosity again and opens the box. This sends her into a deep sleep until she is saved by Cupid. Psyche is often shown with butterfly wings because the word psyche in Ancient Greek means both soul and butterfly. Gibson, who depicted this pair many times in his works, always depicted Cupid with a ‘top-knot’ hairstyle found on classical sculptures like the Apollo Belvedere.

-

Bequeathed by John Gibson RA, 1866.

-

Tell me more about this Gibson.

Gibson was Britain’s most celebrated sculptor during the mid-19th century. He was born near Conwy in Wales, the son of a market gardener, and moved to Liverpool with his family when he was nine. There, Gibson was apprenticed to a cabinet maker and later a stone mason – but his talent for art and passion for the classical world led influential patrons to fund his travel to Italy. He arrived in Rome in 1817 and studied with Antonio Canova, intending to stay in the city for three years. He ended up setting up his own studio there and staying for life, developing an international reputation and counting Queen Victoria and Prince Albert among his patrons. “Go to London? No – what is local fame? If I live I will try for more than that. I may fail – yes – but Rome shall be my battle-field, where I am surrounded by the most powerful competitors,” he said in 1850.

Why did Gibson make this work?

Canova had depicted the story in Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss in 1793 (pictured below), and after that the narrative saw a huge surge in popularity across neoclassical sculpture. By 1827 there were so many versions that one critic wrote that he could retell the whole story simply by describing the various statues by his contemporaries. When Gibson arrived in Rome and began studying in Canova’s Roman studio, he became fascinated by this story. He went on to explore the theme throughout his life in his many drawings and sculptures.

Do we know much about how Gibson worked?

In his memoirs in 1850, Gibson describes the difficulty of first working with clay models, before the full-sized marble sculptures: “After I had worked at the clay a few days down it all fell… a Blacksmith was called, and the iron work made, and numerous crosses of wood and wire. Such a thing I had never yet seen. One of his pupils then put up the clay upon the iron skeleton and roughed out the model before me, so that the figure was as firm as a rock.”

-

I may fail – yes – but Rome shall be my battle-field.

John Gibson

-

What happened to his studio when he died?

Gibson wanted to leave his works and his wealth to “some important good” and by the mid-1860s had decided to donate most of the contents of his Roman studio, and a sizeable amount of money, to the Royal Academy in London through his will. When he died in 1866, crates filled with marble sculptures, plaster casts, drawings and personal effects were shipped to London where they were displayed together at Burlington House in a dedicated “Gibson Gallery” which was open until the 1950s.

You can explore works by Gibson in London collections through a new virtual exhibition.

-

Antonio Canova, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, 1796.

Marble. 137 cm. Image courtesy www.hermitagemusum.org, courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Inv.no. N.Sk-1252..

-

Legacies continue to support all that the Royal Academy achieves and have made a vital difference in caring for the works held in our Collection. Find out more about giving in your will.