Tracing British art through 250 years of the Summer Exhibition

Tracing British art through 250 years of the Summer Exhibition

By Jenny Uglow

Published 15 June 2018

The Summer Exhibition has filled the RA’s galleries every year since 1769 – it’s been a witness (and a player) in many of British art history’s biggest moments. Jenny Uglow takes a look at the art that’s caused drama, changes, protests and celebration over the past quarter millennium.

-

“A monster!”, “A farrago!”, “Should be done away with!” – “A delight!”, “A triumph!”, “A vibrant institution!” For 250 years the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition has divided critics and delighted viewers. Whichever way you look at it, it is a phenomenon. For two months every summer since 1769, first in Pall Mall, then in Somerset House, then in Trafalgar Square and since 1869 in Burlington House, the Academy’s rooms have overflowed with paintings, sculptures and architectural drawings. Reputations have been made and lost, new talents have emerged, experiment and tradition have overlapped. Open to all to submit their work, it is the most democratic art exhibition in the world. Nowhere else can you see such variety in a single show, cutting across movements, offering perennial surprises.

To imagine the huge Summer Exhibitions rolling on through time produces an almost physical feeling of the tides of change. One year a new style ripples through the show. A surge of imitation follows, then the mood dulls and the horizons flatten until suddenly another unexpected wave crashes on the shore, bringing the shock of the new. Running concurrently with this year’s Summer Show, the major exhibition The Great Spectacle dramatises this rich history. Its curators, Mark Hallett and Sarah Victoria Turner, faced a mighty task in choosing from thousands of works. Planning their show with the Academy curator, Per Rumberg, they decided to take the visitor on what they call a “chronological walk”, focusing on the artists and works that they feel have had the most profound impact. Each room of the exhibition covers a different phase and has a distinctive theme, and each reveals battles against convention and changes in British society.

The excitement the Summer Exhibition has aroused can be seen in paintings of the show itself. Gilt frames pack the walls, while jostling crowds bend over to peer at works near the floor or crane their necks to see the unlucky canvases ‘skied’ near the ceiling. And as Thomas Rowlandson implied in The Exhibition Stare-Case, Somerset House (c.1800), more may be on view than pictures.

-

Thomas Rowlandson, The Exhibition ‘Stare-Case,’ Somerset House, c.1800.

Richard Earlom, The Exhibition at the Royal Academy in Pall Mall in 1771, 20 May 1772.

-

When the Academy was founded in 1768, with Joshua Reynolds as President, the 36 Academicians included two women, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser. (A promising start, but a false one – no other women would be fully admitted until Laura Knight in 1936.) Before the mid-18th century the great art collections were in private houses, seen only by the elite, so a big public show was part of the Academy’s programme from the start, following the lead of a successful annual exhibition started by its forerunner, the Society of Artists. Within three years the annual display had swollen to 250 paintings, chosen by a ‘Committee of Arrangement’, later known as the ‘Hanging Committee’. In tune with the hierarchy of the arts, the committee gave pride of place to grand history paintings, like Kauffmann’s Hector Taking leave of Andromache (1768). But almost immediately Benjamin West defied the convention of painting Biblical and Classical scenes with his sensational The Death of General Wolfe (1770), showing an event from the recent Seven Years’ War, historical art with a modern twist. Envying West, all artists aimed to create a stir, to outdo their peers and confront their elders. In 1772, for example, the young Thomas Gainsborough challenged Reynolds’ idealised portraiture with his lyrical Elizabeth and Mary Linley (c.1772). Within two decades, Gainsborough was stumped in his turn by Thomas Lawrence’s dazzling, characterful study of the actress Elizabeth Farren.

-

Angelica Kauffman, Hector Taking Leave of Andromache, 1768.

Thomas Gainsborough, Elizabeth and Mary Linley, c.1772 (reworked 1785).

-

Grand portraits dominated the early shows. But lowlier genres began to attract notice – the animal paintings of George Stubbs, and the powerfully emotional works of Joseph Wright of Derby, whose The Dead Soldier (1789) spoke of the cost as well as the glory of wars. A concern for – and fear of – the anonymous poor increased during the Napoleonic Wars, and the most talked about picture of 1806 was David Wilkie’s The Village Politicians, where labouring men – radicals – discuss the newspapers in a Scottish pub. Did the smart exhibition-goers regard these men as dangerous? Perhaps, but soon the Academy’s walls were covered with urchins, humble firesides, market crowds. When Wilkie showed his Chelsea Pensioners Reading the Waterloo Dispatch in 1822, a bar had to be put in front of the painting to stop the crowds touching it. As Hallett explains, any celebration of heroism was countered by William Mulready’s gaunt portrait of an injured veteran, The Convalescent from Waterloo: “a painting that demonstrated the capacities and contradictions of the Summer Exhibition itself: even as it promoted the jingoistic narratives of imperial victory, the display was fully capable of housing works of art that profoundly challenged the political orthodoxies of the time”.

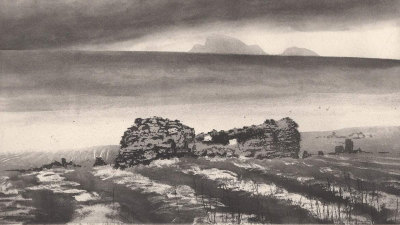

During the long wars people also turned to landscape, both as a consolation and a symbol of what they were fighting for. Unable to paint in Italy or the Alps, artists looked to their own landscapes. Some transferred the ‘sublime’ to the Lake District and Wales – Girtin’s A Grand View of Snowdon, was shown in 1799. Others looked nearer home: Constable presented Dedham Lock and Mill in 1818, and seven years later his great Leaping Horse, while in the 1830s Turner showed radiant sea- and sky-scapes, such as St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall. The Turner/Constable tension was summed up by the famous scene in 1832 on Varnishing Day, when artists added finishing touches to their works in the galleries. Turner, piqued by the flags and colours of Constable’s Opening of Waterloo Bridge, daubed a tiny red dot in his seascape Helvoetsluys, adding a flick of varnish to turn it into a buoy, distracting attention from his rival. “He has been here and fired a gun,” said Constable.

-

J.M.W. Turner, St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall, c.1834.

John Constable RA, The Leaping Horse, 1825.

-

After the Academy moved to a wing of the new National Gallery building in Trafalgar Square in 1837, the Summer Exhibition began to seem dull and predictable, and there were complaints, too, that the choice was ruled by a clique, favouring their cronies. In 1840, a young artist ‘John Smart’ appealed in the Morning Post to the President, Martin Arthur Shee, “What chance can there be for strangers?”

Yet strangers were approaching. In 1849, John Everett Millais’s Isabella and Hunt’s Rienzi, signed with the cryptic initials ‘PRB’, announced the arrival of the revolutionary Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. With their jewelled colours and medieval stories – a different, literary ‘history painting’ – their works shone out among the crowded canvases. The PRB tackled religious subjects too and in 1850 critics blasted Millais’s Christ in the House of his Parents, which Dickens denounced in his journal, Household Words, as ugly and blasphemous: Christ was a hideous, blubbering boy and the carpenters could be found “in any hospital where dirty drunkards, in a high state of varicose veins, are received”. The storm passed. Within years Pre-Raphaelite paintings were a fixture.

From 1865 the paintings sold were marked with a red dot, and new buyers with wealth from industry and business competed with landed purchasers, while a booming print market allowed the middle classes to hang images of famous paintings on their walls. Print dealers rushed to purchase rights: the Illustrated London News and the Graphic showed engravings within a week. Startling works crept in quietly, like Whistler’s brilliant, experimental etchings of London’s wharves, exhibited in 1860, and powerful oddities turned up, including Elizabeth Butler’s soldiers in A Roll Call (1874). But the high Victorian hits were heroic animals like Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen (exhibited in 1851); scenes of Britain at play, such as William Powell Frith’s Ramsgate Sands (shown as Life at the Seaside, 1851-54); or Millais’s My First Sermon (1863 ) and My Second Sermon (1864), where his small daughter is attentive, then asleep, in her pew.

In the late 19th century the Summer Show hit a peak. Around 350,000 people visited. In 1883 Frith painted the great and good in A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881, (1883) whether they were there or not. As well as Gladstone, and Frederic Leighton, the then President, Frith showed actress Ellen Terry, and scientists, artists and writers, including Oscar Wilde holding forth to women in ‘aesthetic’ gowns. “I wished to hit the folly of listening to self-elected critics in matters of taste, whether in dress or art,” Frith said. “I therefore planned a group, consisting of a well-known apostle of the beautiful, with a herd of eager worshippers surrounding him.” The crowd, not the paintings, made the show.

-

William Powell Frith, A Private View at the Academy, 1881, 1883.

© A Pope Family Trust, c/o Martin Beisly.

-

Until it was pipped to the post by the Chelsea Flower Show, the opening of the Summer Exhibition marked the start of the ‘season’. The exhibition itself was like a grand party, with artists clamouring for invitations. Traditionally, they submitted their work on Sending In Day in March. Today, this first stage takes place by digital submission – around 20,000 were received in 2018, of which 4,000 were requested for the galleries, around 1,200 making the final hang – but in the past, queues of hopefuls stretched down the road, often in the rain, clutching their canvases. These were whisked into the vaults and brought out in May, when the Selection Committee met, fortified by a brew of beef tea and sherry. Puzzling over how to represent the many amateurs and part-timers in The Great Spectacle, the curators decided, explains Hallett, to include a work by “perhaps the most famous amateur ever to exhibit at the RA: Winston Churchill, whose presence also demonstrates how much part of the establishment the RA exhibition became. But we realised that the great majority of exhibitors are, and always have been, people who make their living through art.”

As the century turned, there were heated debates – was John Collier’s The Prodigal Daughter (1903), a portrait of the ‘New Woman’? – and a scandal in 1914 when the suffragette Mary Wood attacked John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Henry James with a meat cleaver. But nothing, not even the War, could stop the show.

-

Unidentified photographer, Detail of the portrait of Henry James O.M. by J.S. Sargent R.A. after being damaged by a suffragette, May 1914., ca. May 1914.

Part of the RA Collectionsilver gelatin print mounted on card. 250 mm x 283 mm. © Photo: Royal Academy of Arts, London.

-

In May 1919, the exhibition was celebrated as a return to normality, its opening marked, declared The Times, “by all its old brilliancy from a social point of view”. Writing in the Athenaeum, Virginia Woolf found less brilliancy in the art itself. There were striking works, like Paul Nash and Modernism like specks of dust on their jackets. In the inter-war years, fine works hung in the Summer Exhibition, like Laura Knight’s Lamorna Birch and his Daughters (exhibited 1934), but the resistance to the new grew even stronger. In 1938 the rejection of Wyndham Lewis’s portrait of T.S. Eliot caused intense fury: Augustus John, an Academician of many years, resigned in protest. It made no difference: in 1949 the President, Alfred Munnings, stunned the Academy banquet with a diatribe denouncing modern art and “foolish daubers” like Picasso and Matisse. It seemed many agreed: the greatest hit in the next decade was Pietro Annigoni’s portrait of Elizabeth II Queen Regent (1955).

-

-

Explore 250 years of the Summer Exhibition online

In celebration of the RA’s 250th birthday and coinciding with The Great Spectacle, a new open-access publication by the Paul Mellon Centre looks back at 250 years of the Summer Exhibition.

Delve into 250 years of stories, artworks and data, alongside lively year-by-year essays and a complete set of digitised, searchable Summer Exhibition catalogues.

-

-

In the Observer in 1959, the architect Hugh Casson struck out at the Academy’s claims. It was false, he said, to praise it for upholding tradition: “Tradition is not a corpse to be propped up. If it has value and strength it will survive.” As for the Summer Exhibition, it had declined to “a provincial show of no interest to anybody except ourselves”. Perhaps, severely cut down, it should move to October? “Once clear of the Ascot-Wimbledon-Season circus, it would be taken more seriously and could become more serious.” It did not move, but, slowly, change came. The 1960 show included artists of the ‘Kitchen Sink’ school: Jean Cooke, John Bratby and L.S. Lowry; in 1964 Euan Uglow’s Nude (1962-63) revitalised life studies; and in the next year Peter Blake’s Toy Shop (1962, exhibited 1965) heralded the arrival of Pop Art at the RA. The crowds began to change: “Beatniks and Dowagers Crowd the Academy”, announced the Daily Telegraph following the private view in 1965.

-

Peter Blake, The Toy Shop, 1962.

Tate: Purchased 1970 / Photo © Tate, London 2017.

-

When Hugh Casson became President in 1976, a younger set of artists was selected for the show, particularly architects – three of the Academy’s founders had been architects, and they always had a place in the Summer Exhibition. The Great Spectacle acknowledges this with a special room containing works ranging from William Chambers’s design (c.1791) for a Temple of Diana at Blenheim, to Basil Spence’s chalk drawing of Coventry Cathedral (exhibited 1952) and Zaha Hadid’s imagined aerial view of Cardiff Opera House shown just after her death in 2016. Yet despite Casson’s efforts, in the late 20th century the Summer Show lacked bite. It was, thought one critic in 1993, “a mix of acres of paintings by competent part-timers who all seem to live in Purley”. A much-needed jolt came in 1997 with R.B. Kitaj’s explosive The Killer-Critic Assassinated by his Widower, Even. That same year, the RA’s huge Sensation show highlighted Saatchi’s iconoclastic Young British Artists: soon YBAs like Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin seemed a natural part of the Summer Exhibition. At the same time an old tradition sprang to life with David Hockney’s huge Grand Canyon landscapes. Ten years on, when Hockney’s Bigger Trees near Warter (2007) covered an entire wall, the show drew its largest crowds for 30 years.

In 2001, Peter Blake, the ‘Senior Hanger’, had the brainwave of urging Honorary Academicians – leading foreign artists – to submit their best works for hanging together across two galleries: since then internationally known names such as Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz have provided some of the exhibition’s highlights. Artists on the committee have made bold innovations, and increasingly, politics has entered the show, notably in Yinka Shonibare’s screenprint, Bunch of Migrants, hung in the summer of the Brexit referendum in 2016, its title borrowed from David Cameron’s sneer at the refugees in Calais. The Summer Exhibition is more radical than many “political” art exhibitions, says Grayson Perry, co-ordinator of this year’s Selection Committee. Its openness to all-comers means that the Academy has worked for years with different communities and outsiders: “People may dismiss it as an overblown summer fête, but although it’s always a mish-mash, it’s always different”. It’s unpredictable too, “impossible to impose an overall theme because that depends on what comes in”. This March, after viewing countless submissions, Perry walked across the Annenberg Courtyard, dazed by the thought that in three months’ time this would be the red carpet for the preview. The speed at which the show is put together means there is no time to construct grand theoretical narratives: it is bound to be playful, spontaneous and, one hopes, fun.

-

Zaha Hadid, Aerial view, Cardiff Bay Opera House, Cardiff Wales, Competition, 1994 – 1996.

Yinka Shonibare RA, Bunch of Migrants, 2016.

-

Throughout its history, the Summer Exhibition has often taken those who plan it by surprise, from Joshua Reynolds onwards. Its very breadth and sweep militate against coherence, and that is what gives it its energy and enduring vitality. At the time a show may look like a “mish-mash” but later, looking back, one can see the dominant patterns and preoccupations, and trace movements, from the rise of genre painting to the move of Pop Art into the mainstream. The Great Spectacle grants us this longer view, charting the history of British art and society through the optics of the country’s most diverse and unpredictable show.

-

Jenny Uglow is an author, critic, historian and editor.

-

-

Visit The Great Spectacle

Opens 12 June 2018

Journey through the story of 250 years of the Summer Exhibition, the world’s longest running annual display of contemporary art.

The Great Spectacle is an innovative, illuminating and visually stunning celebration of the Academy’s first 250 years and demonstrates the impact of the Summer Exhibition on art in Britain and internationally.

-